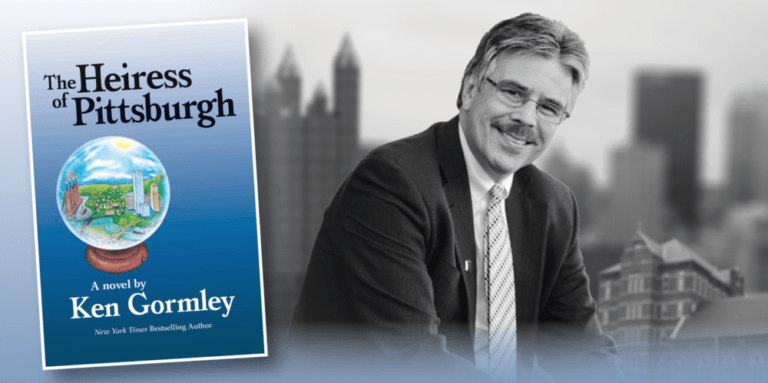

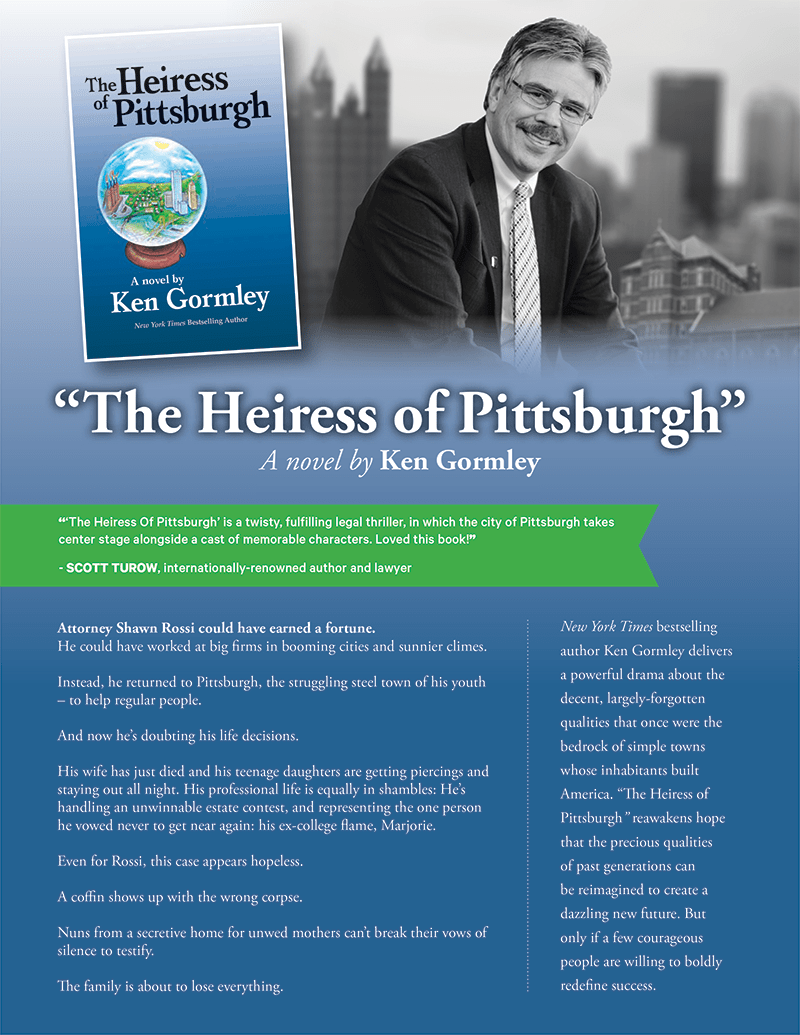

About the Author: “Ken Gormley is president of Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. A lawyer, constitutional scholar, and author, Gormley’s work has earned him national and international acclaim. His book The Death of American Virtue: Clinton vs. Starr (Crown 2010) was a New York Times bestseller and was selected as one of the top non-fiction books of the year by the New York Times and Washington Post. Gormley’s first book, Archibald Cox: Conscience of a Nation (Addison-Wesley 1997), won multiple book awards. Earlier in his writing career, Gormley received the first Rolling Stone magazine college journalism award for feature writing, chronicling adventures including setting a Guinness World Record in brick carrying and wrestling a bear.

The Heiress of Pittsburgh is Gormley’s first work of fiction. Over thirty years in the making, it speaks to a subject that is universally relevant. A love story about people, places, and simple virtues that flourished in working-class towns and ordinary communities that once built America, this beautifully crafted novel provides hope that precious qualities of the past can be recast to create a rich new future; but only if success is boldly redefined.

Gormley has appeared on NBC’s Today Show, MSNBC’s Morning Joe, NPR’s Fresh Air, multiple PBS and BBC documentaries, and hundreds of television and radio shows in the United States and worldwide. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The LA Times, Politico, HuffPost, and numerous other publications. The former mayor of his town in Forest Hills, Pennsylvania – a small community outside Pittsburgh – he lives there with his wife and family.”

More info

Praise for The Heiress of Pittsburgh:“The Heiress of Pittsburgh is a twisty, fulfilling legal thriller in which the city of Pittsburgh takes center stage alongside a cast of memorable characters. The hold that the past has on the present—loves lost and found, the complex relationship between remembering and speaking the truth—are the themes that add power to a truly gripping story. Loved this book!” —Scott Turow, internationally-renowned author and lawyer whose legal thrillers have been translated into more than 40 languages

“A whole lot of the Burg and a whole lot of other good things in The Heiress of Pittsburgh—family histories, courtrooms, neighborhoods, loves lost and found, styles of remembering and speaking. A complex, intriguing narrative about a place and people I connect with intimately. Thank you for writing and sharing.” —John Edgar Wideman, acclaimed author and PEN/Faulkner Award recipient

“Gormley’s skills with language, dialogue and narrative bring his wonderful, unpretentious and utterly genuine characters to life. This is a book for all who love the authenticity of a regional culture and the grace of a writer who can bring it to life.” —Maxwell King, bestselling author of The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers

“Gormley takes us on an emotional journey through Pittsburgh, bringing out the secrets of family and the importance of neighborhoods, always showing us how the choices we make can make a difference.” —Franco Harris, legendary Pittsburgh Steelers running back, Pro Football Hall of Famer and four-time Super Bowl Champion

“‘Did you ever wonder what makes a place like Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh?’ the hero of Ken Gormley’s debut novel asks. The author sure knows. Part courtroom drama, part family saga, part teen romance, The Heiress of Pittsburgh is a generous, warm-hearted paean to the Steel City.” —Stewart O’Nan, author of Everyday People and Emily, Alone

“Gormley has written a moving and compelling story which captures the heart and essence of the real Pittsburgh and its people with unmatched authenticity.” —Lee Gutkind, founding editor, Creative Nonfiction Magazine

“We all want to write that first novel about our home town…about the one that got away… about mystery and loss, sacrifice and truth. Ken Gormley just waited 30 years to do it. Take a look people.” —David Conrad, film, TV, and stage actor

“The Heiress of Pittsburgh features an entertaining cast of characters along with many twists and unexpected turns. Ken Gormley’s novel provides a window into the bygone culture of the ethnic melting pot that existed for more than a century in the steel valleys of western Pennsylvania. It is a compelling and enjoyable story.” —Art Rooney II, President, Pittsburgh Steelers

“The Heiress of Pittsburgh is a love story that contains all the unique flavors of Pittsburgh—the history, the folklore, the stories inherent in each neighborhood, its colorful residents, and the tale of the heyday of the industrial three rivers region. The charming hero, lawyer Shawn Rossi, bears the weight of the city’s underbelly while striving to bring justice to his beloved birthplace. Gormley illuminates this journey with humor and an ample dose of humanity.” —Constanza Romero Wilson, widow of Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright August Wilson; Tony Award-nominated costume designer

“The Heiress of Pittsburgh is an inspirational, multigenerational epic about leaving home and finding it again, with a deep love for Pittsburgh on every page.” —Nick & Rachel Courage, founders, Littsburgh

The Heiress of Pittsburgh

From the Publisher: “Attorney Shawn Rossi could have earned a fortune.He could have worked at big firms in booming cities and sunnier climes.

Instead, he returned to Pittsburgh, the struggling steel town of his youth–to help regular people.

And now he’s doubting his life decisions.

His wife has just died and his teenage daughters are getting piercings and staying out all night. His professional life is equally in shambles: He’s handling an unwinnable estate contest, and representing the one person he vowed never to get near again: his ex-college flame, Marjorie.

Even for Rossi, this case appears hopeless.

A coffin shows up with the wrong corpse.

Nuns from a secretive home for unwed mothers can’t break their vows of silence to testify.

The family is about to lose everything.

New York Times bestselling author Ken Gormley delivers a powerful drama about the decent, largely-forgotten qualities that once were the bedrock of simple towns whose inhabitants built America. The Heiress of Pittsburgh reawakens hope that the precious qualities of past generations can be reimagined to create a dazzling new future. But only if a few courageous people are willing to boldly redefine success.”

Chapter One

September 2008 (North Braddock, PA)

THE EXHUMATION

“Beautiful job! You cracked her open real nice,” a cemetery worker hollered at his partner.

“Beautiful job! You cracked her open real nice,” a cemetery worker hollered at his partner.

Another worker wearing a bandana jumped into the muddy pit with his hammer and chisel and pounded away at the vault.

My client, Choppy Radovich, stepped closer to the hole and nearly lost his footing. I could see that his limp had become more pronounced with the worsening of his “arthur-it is,” as he called it. His leg had been blown to hell during the D-Day invasion of World War II, leaving him with a herky-jerky limp and the nickname “Choppy” that he wore like a badge of honor.

Choppy inserted a fresh chew of Copenhagen under his lip and eyed the grave. “You mind if I grab holda’ your arm, Shawn? I never figured turning eighty-six would be such a pain. I don’t wanna sprain my only groin in this-here mud.”

A flock of ring-necked pheasants skittered across the edge of the cemetery before getting spooked by the backhoe’s engine and taking flight.

My co-counsel, Bernie Milanovich, had known Choppy for years through the Croatian community, which had deep roots in this town. (Lots of names ended in “ich” or “ach” around here). Bernie chewed nervously at his mustache, causing the white hairs to appear darker at the edges. Although he and I ran separate little estate firms in downtown Pittsburgh, we’d joined forces on dozens of cases over the years to assist each other when needed. I always tried to say yes when Bernie asked for help. But in this case, I should have stayed a thousand miles away.

Choppy was a model client, but he was also the grandfather of my first girlfriend, Marjorie, who had walked out of my life decades ago. I should have known this was a horrible idea. But something inside me told me I needed to do this for Marjorie’s family.

“Wipe off that lens!” Bernie shouted at the video crew. “You think the Superior Court wants to look at close-ups of water molecules?”

The proprietor of the local Serbian funeral home darted around like a nervous wedding coordinator, supervising the exhumation. “Good work, boys,” he said. “Let’s get that sucker pulled up.”

The muddy hillside of the North Braddock Catholic Cemetery provided a perfect vantage point from which to survey the region’s past, or at least what remained of it. High above the bend in the Monongahela River, which flowed south to north toward the city, I could see ancient grave markers, Roman Catholic crucifixes, Byzantine crosses, and other tributes to the dead that were stained with mill soot but otherwise nicely preserved. Instead of pointing skyward toward heaven, these memorials sloped downward to provide a sweeping view of the Edgar Thompson steel plant—the last operating mill in the valley, where Andrew Carnegie had created his steel empire in the 1880s—and the silenced blast furnaces of the Carrie Furnace, which had once supplied molten pig iron to the adjacent mills. In these communities, most local families had found work, constructed simple homes, and built livelihoods during the indus¬trial migration of a past era.

Even though I’d left this place to get a law degree at Harvard, where I’d experienced a different realm, I somehow couldn’t escape my roots.

The lead worker, his bandanna drenched from the rain, hooked up a block-and-tackle then cranked up the dirty concrete box until it rose one, two, three feet into the air. He swung it onto the ground with a thud!

“Don’t crack the lid, fellahs!” Bernie stepped amidst the workers. “We want these bones and teeth in one piece. Right, Your Honor?”

Senior Judge Warren Wendell, the presiding judge, looked around uneasily.

Over a period of two decades, the vault had leaked and collected brackish water. Inside, a bronze-colored casket bobbed in the dirty water like a Halloween apple. A pungent, offensive odor—the smell of rot and mud and death—swept into the air. The guy with the bandana jammed a kerchief against his mouth.

“Just a little water seepage,” interjected the funeral director, waving his hand. “Even the deluxe model gets a little moisture after twenty years of this Picks’burgh weather.”

He inserted a crank at the casket’s base and began turning it.

Choppy limped forward to eyeball the perpetrator who had wrecked his daughter’s life and ruined his family’s future fifty years earlier. He clutched my arm and squeezed it. “Lookie here, Shawn. I know things got screwed up with you and Marjorie back when yinz two were younger. Maybe you could patch things up when she gets back here for her testimony. You were always good for each other. The Lord works in funny ways. Maybe this-here trial was meant to be for a reason.”

A dozen ethnic dialects in this region had been mashed together to produce a distinctly Pittsburgh jargon. “Wash” was pronounced “worsh,” “downtown” was “dahntahn,” “rubber bands” were “gumbands,” and “redd up” meant to “clean.” Choppy spoke the lingo with a natural flair.

I put my arm around the old man. There was something special about Choppy. He was a true “mill hunky,” as he proudly identified himself. Choppy was open, direct, and straightforward. Whatever he said, you could take to the bank. His granddaughter Marjorie, though, wasn’t such an open book. But that was a different story.

“We’ll get our proof from the DNA,” I whispered to the old man. “Marjorie won’t even have to waste her time flying here from California to testify. It will all work out,” I said. Choppy pretended he didn’t hear me.

The cemetery crew used the chisel to pry open the coffin. As the lid rose, rain doused the coffin’s moldy silk liner. One worker covered his mouth, suppressing an urge to gag.

“Jesus H. Christ!” Judge Wendell exclaimed, making the sign of the cross. He hurriedly lit a Kent cigarette and sucked down a bolus of menthol smoke. A light-skinned Black man with graying hair, the judge was known for maintaining his cool under fire. Now, his eyes opened to the size of quarters. He seemed interested in viewing the decedent, whose alleged act of sexual gratification a half-century earlier had spawned this messy will contest and consumed a week of his Orphan’s Court calendar.

“That’s one ugly biddy!” exclaimed the worker with the bandana, peering inside.

“Who the hell is this?” Bernie pointed at the imposter.

The undertaker whipped out his cemetery map, certain that they must have dug up the wrong plot.

The woman in the coffin wore a purple chiffon dress discolored by green mold and a white wig that had jarred loose. Her wrinkled face with its hooked Eastern European nose had become eerily wax-colored from embalming fluid and the passage of time. “That’s the grave wax,” the deputy coroner whispered to the judge. “The technical term is adiopocere.”

“This sure as hell ain’t Ralph Acmovic, the guy we’re looking for,” said Bernie.

“That bastard,” the Serbian funeral director cursed, adding a foreign expletive while smacking the coffin. “Looks like my uncle did it again. He swore he straightened hisself out after he got busted.”

Bernie grabbed the undertaker by the rain slicker. “What the hell are you saying? Where’s Ralph Acmovic, you duppa?”

“He could be anywheres,” the funeral director said, wriggling free. “Probably dumped over the hillside. Who knows? My uncle lost his license back in the ’70s for doing this crap. Hey, look, I ain’t going to jail like him. We cleaned up our act, Bernie,” he said, raising his right hand. “Swear ta’ God.”

“So, who the hell’s this?” Bernie demanded.

We all stared at the corpse. Even 30 years after death, she would have benefitted from a radical nose job.

“This here looks to be one of my great-aunts,” the funeral director said sheepishly. “She bears a family resemblance—sort of. I’m guessing my uncle wanted to give her a nice send-off, you know, to make it look good for the family? He probably dumped this Acmovic guy over the hill into the slag heap, reused his casket, and kept the cash. It’s not the first time a Serbian would have pulled a fast one on a Croatian and done something like that.”

The deputy coroner and his assistant began packing up their bone saws, scalpels, and plastic gloves, pleased to have a good story to take back to the office.

As the cemetery workers fired up their backhoe to lower the coffin back into the grave, three spectators at the top of the hillside drifted toward us. A young muscular guy holding a golf umbrella, wearing a McCain-Palen button on his lapel, escorted our opposing counsel from Philadelphia. She smirked as she walked past us. A third person—a rodent-like man with moles on his face—gave Bernie and me the finger behind his back. With that, the trio climbed into a Lexus.

Choppy stared blankly at the waxen face of the corpse. I put my arm around him and hugged the old man. “Sorry it turned out this way, Choppy,” I said. “But we still have some legal maneuvers up our sleeve, don’t give up hope.” He nodded his head slowly. Then he broke down, his shoulders shaking like the flanks of an exhausted workhorse, expelling deep sobs that seemed unnatural for a man who’d lived to reach the age of eighty-six after having witnessed so many of life’s injustices.

I turned away, ashamed that Bernie and I had brought him to this place.

Judge Wendell blessed himself hurriedly, then turned toward Bernie and me.

“Well, you gave it a shot, gentlemen,” he said, tugging up the collar of his trench coat. “We’re starting trial on Monday at ten o’clock. Unless you have the good sense to withdraw this lawsuit, so this family doesn’t get hurt even worse.” He glanced toward Choppy, who stared at the empty hole. Then the judge walked away.

Once the last Jeep had pulled out and I’d walked Bernie and Choppy to their cars, I spun around and dragged myself up the hillside. Clumps of red mud clung to my wingtips. I cursed and tried to kick it off against a tombstone inscribed with the words “Tu Spokiva” (“here sleeps”); this was obviously the Slovak section of the working-class dead.

Ordinarily, I would have made a detour to the cemetery section that included the Rossi and McFadden plots—the sacred place where my mom, dad, and their families were buried. Today, I blessed myself and blew a kiss in their direction.

At the top of the hill, I reached a thornless honeylocust tree next to a familiar stone marker. I fell on one knee. “Hi, sweetheart,” I said. The red mud soaked through my trousers—another pair of pants that would need to be dry-cleaned.

I closed my eyes. My fingers traced out the words etched into grey marble:

“Christine Kendall Rossi. Beloved wife. Best mom in the world. 1958–2006”

“I’m here, sweetie,” I whispered, stroking the marble like a precious pearl. “Your mom and the girls made haluski last week. It was a wild scene. The house stunk from cabbage for days. You would have loved it.

“Oh, you probably saw the whole thing, right? I know you’re watching with those eagle eyes of yours. I’m trying to spend more time with the girls. Honest, Christine.”

I stood up, kissed one of my palms, and placed it against the cold, wet stone.

“Don’t get the wrong idea about me handling this case, okay?” I patted the marble. “I just feel like I should do this for the family. Choppy’s one of the great mill-hunkies of all time; you know that. They’re good people. There’s nothing more to it than that.”

I blessed myself and stared at the stone marker as if, somehow, it provided a portal through which Christine could see me.

“Just keep an eye on your husband, promise me, sweetheart? I need lots of bucking up right now. Being a parent without you here is a lot harder than I imagined. So is coping with this case.”

This excerpt of The Heiress of Pittsburgh is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted without permission.