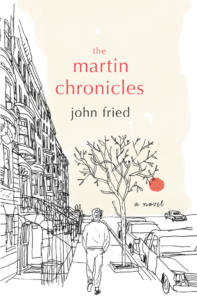

“Wise and winning, The Martin Chronicles is a sumptuous evocation of those adolescent afternoons when every moment was equally fraught and full of possibility. A charming, marvelous debut.” — Colson Whitehead, Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award-winning author of The Underground Railroad

From the Publisher: “This poignant debut [by Dusquesne professor John Fried! — ed.] perfectly captures the intense emotion, humor, and earnestness of young adulthood as Marty, age eleven to seventeen, navigates a series of life-changing firsts: first kiss, first enemy, first loss, and, ultimately, his first awareness that the world is not as simple a place as he had once imagined.”

Don’t miss out: Fried will be visiting Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures’ Made Local series to read from his new book, discuss the book in conversation with author Irina Reyn, and take questions from the audience on Tuesday, January 8 and tickets are free with registration!

“A beautiful debut. The Martin Chronicles transforms a series of adolescent snapshots into a raw, unforgettable mosaic.” — Stephen Chbosky, New York Times bestselling author of The Perks of Being a Wallflower

About the Author: John Fried‘s short fiction has appeared in numerous journals, including The Gettysburg Review, North American Review, and Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art. He teaches creative writing at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh and received his MFA from Warren Wilson College’s Program for Writers. Prior to teaching, he was a magazine writer and editor in New York, and his work appeared in various publications, including The New York Times Magazine, Rolling Stone, New York, Time, and Real Simple.

Dave tackled me, bringing me to the floor. He emptied my pockets, pulling out everything he could find—gloves, a pack of gum, a bag of pennies, a New York Knicks stapler. Max was on me as well, but he was single-minded, only interested in the safe cradled in my arms. He dug his hands between mine and the gray metal box, trying to pry off my arm. It wasn’t going to happen. They could take anything—my wallet, my backpack, even my clothes—but they weren’t getting the safe.

Dave tackled me, bringing me to the floor. He emptied my pockets, pulling out everything he could find—gloves, a pack of gum, a bag of pennies, a New York Knicks stapler. Max was on me as well, but he was single-minded, only interested in the safe cradled in my arms. He dug his hands between mine and the gray metal box, trying to pry off my arm. It wasn’t going to happen. They could take anything—my wallet, my backpack, even my clothes—but they weren’t getting the safe.

The game was called Mugger. The rules were simple: Get from one side of my bedroom to the bathroom door on the other side while two muggers tried to steal everything you had. We took turns playing the victim and the muggers. Before each round, the victim packed his pockets with randomness—Matchbox cars, pens, rolled-up socks, soap bars, keys, flashlights—whatever we could find around my room. It was almost tough to walk with your hands full and pockets overflowing, but that was the point: You were basically begging to be mugged.

We each carried one special item, the real prize if you got it away from someone. Max carried a small portable radio that didn’t work. Dave had an old leather wallet packed with colorful Monopoly money. I had my safe, this small gray metal box, the size of a shoebox and as light as a football, which I hugged across my chest. The muggers could do whatever they needed to do—tickling, grabbing, full tackles—although above the neck was off-limits. I had already had to explain one scratch on my cheek to my parents, who looked at me suspiciously when I told them it was from a game with my friends.

That afternoon, even with my friends all over me, I was still able to drag myself across the room, my feet digging into the carpet for traction. When I got close to the bathroom, I stretched out my arm and touched the door, shouting, “Base!”

Max fell off me, leaning against a dresser, catching his breath. “Damn, Marty,” he said, pointing at the safe. “You never give that thing up.”

Dave said, “What’s in there, anyway?”

“Nothing important,” I said, which was the truth, more or less. It was packed with things I had collected for years: A complete set of 1982 New York Mets baseball cards—a thoroughly forgettable team. A supposedly authentic piece of moon rock given to me by a neighbor for my eighth birthday. A bunch of vacation photos from Cape Cod with my cousin Evie. Nothing special. The only thing I cared about was what I had discovered inside the safe when I found it in the attic at my grandfather’s house: a bullet. It was small, this short little stub, half the size of a crayon, with a dull yellow case and dark gray tip. The whole idea of having it made me feel powerful, a little dangerous.

When I found the safe at my grandfather’s house it was locked, but after several weeks of working on it, I’d figured out how to open the door. There was something so satisfying about doing it—feeling for the clicks, the snap of things slipping into place, the door swinging open. Later that week, I was supposed to give a presentation for Mr. James’s public speaking class, where we walked the class through the process of something we knew how to do well. I was going to bring in the safe and open it with my eyes blindfolded, maybe show off the bullet.

“Who’s next?” Max said, standing up.

“I think it’s me,” Dave said, pulling out his wallet filled with red, green, and blue fake money, and stuffing it into his pants. I started stripping out of my extra clothes, throwing everything to the floor in a pile, eager for the next round to begin.

It had all started in March, when Principal Conrad announced at assembly that several kids from Welton, a super rich private school across town, had been mugged walking home. We were told to be on alert, but I didn’t think much of it. Welton was on the East Side, a world away from where I lived and went to school. They might as well have been mugged on the moon.

A week later, though, Willy Maffert, a boy in the third grade, three grades below me at my school, was mugged in the park. The mugger took his wallet and his Casio calculator watch. We all wanted the watch because you could play Space Invaders on it. The numbers fell down the screen like rain.

Two more boys at my school went down soon after, fourth graders, mugged playing video games at the Twin Donut only a few blocks away. The muggers stole their backpacks and all their quarters.

Then the first middle schooler fell. Fifth grader Jason Slocum. He was mugged around the corner from school, waiting for the bus home. It was school fair day and there were plenty of people milling around, but the muggers had still managed to get Jason, taking his backpack, his bus pass, even the Strat-O-Matic Baseball game he had bought at the fair. It was as if a storm had been creeping closer and closer for weeks, and it was now upon us.

Rumors swirled about the muggings. At first, I’d heard that it was a kid my age, but soon there were other versions circulating around the school. It was a gang from the Bronx that had moved into Manhattan after they mugged everyone in their neighborhood. It was a grown-up, alone, someone who had escaped from prison. Sometimes the mugger was black, sometimes white, even Dominican or Chinese. He had a gun. He had a knife. He had an extra finger. The story was never the same. The muggers were like ghosts, everywhere and nowhere, constantly changing. I wasn’t scared. I was in sixth grade, after all, and so far the muggers had gone after younger kids. Still, there was this nervous energy pulsing through the school, people constantly talking about the muggings. I’d seen a few kids bawling after school assembly—one third grader supposedly pissed in his pants—but my friends and I delighted in any news, eager to know who had gone down next. That’s when we invented Mugger, the game. We thought we would be prepared if it ever happened to one of us, although none of us believed we would ever get mugged. Fact was, the game was fun, like playing cops and robbers, or cowboys and Indians, only better, more like real life.

Excerpted from THE MARTIN CHRONICLES. Copyright © 2018 by John Fried. Reprinted with permission from Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.