From the Publisher: “Salvatore Pane’s The Neorealist in Winter is a collection of eleven short stories that explore what it means to be human in an age of media oversaturation. Utilizing methods of speculative, historical, and postmodern storytelling, Pane grapples with legacies of immigration, poverty, toxic masculinity, and moral failures, while focusing on working-class issues, family drama, and PTSD. Following eleven Italian narrators, Pane builds a cast of cinematic characters across disparate times and places—a struggling director attends a house party in the la dolce vita of 1960s Rome, gangsters chase a low-level lottery runner in coal valley Scranton, a woman contemplates experimental surgery to purge memories of her childhood trauma in Minnesota, and a pro wrestling promoter descends into self-denial through his autobiography.”

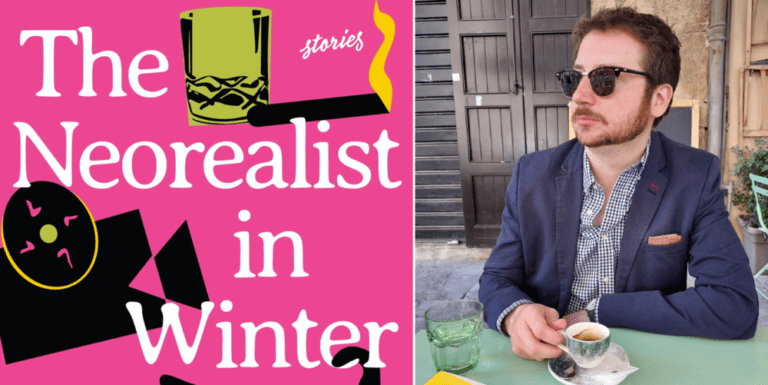

More info About the Author: “Salvatore Pane was born and raised in Scranton, Pennsylvania. He is the author of two novels, Last Call in the City of Bridges and The Theory of Almost Everything, and a book of nonfiction, Mega Man 3. His shorter work won the Turow-Kinder Award judged by Stewart O’Nan, was nominated for the Pushcart Prize, and has appeared in Indiana Review, American Short Fiction, Story Magazine, and many other venues. He’s also written video games and graphic novels, and his textbook, Story Mode: Writing Narrative Video Games for Everyone, is forthcoming from Bloomsbury. He holds an MFA in creative writing from the University of Pittsburgh and currently serves as associate professor at the University of St. Thomas. He lives with his wife and Martin Scorsese the Cat in St. Paul, Minnesota.”

Author website “These stories ache and bend into the convex shapes of despair without necessarily pining for seasons of respite. In the scratch that is ordinary tragedy and extraordinary expectations, a light pulses in these characters filled with language for obsession, adoration, and fury.” —Venita Blackburn, author of How to Wrestle a Girl: Stories

“A wildly inventive book that’s both hilarious and heartbreaking, about the strange comforts we find in desperate moments: a man holds off his sorrows by obsessively watching Goodfellas; a son copes with his absent father via professional wrestling; a woman works through trauma by way of a talking-animal sitcom. Salvatore Pane is a writer alert to all the puzzling paths that healing sometimes takes, a writer of profound insight and honesty and pure gracious human compassion.” —Nathan Hill, author of Wellness: A Novel

“Take a breath between these thrilling stories: you’re about to meet characters on the verge of something great or calamitous, navigating a range of worlds from the hyper-real present to the sepia-toned past. Salvatore Pane delivers each cinematic scene with deft narrative urgency and economy, blending fact and fiction in a way that feels thematically true not only to the Italian American experience, but to the harrowing experience of being alive.” —Christopher Castellani, author of Leading Men

An Excerpt from “Mamma-draga”

Frank bought the skateboard seven weeks after his divorce. It gave him something positive to focus on even before it arrived, when it was only a tracking number, a link to refresh late at night when Frank blinked himself awake and remembered he was no longer in his split-level, but instead his childhood bedroom in Squirrel Hill. He reached for his cellphone on those sleepless nights and flooded the tiny room with artificial light. There it appeared, the Crimson Cross 8” x 31.5” preassembled skateboard moving in an unbroken line across America headed straight for Frank Catalano, fresh divorcé.

Frank bought the skateboard seven weeks after his divorce. It gave him something positive to focus on even before it arrived, when it was only a tracking number, a link to refresh late at night when Frank blinked himself awake and remembered he was no longer in his split-level, but instead his childhood bedroom in Squirrel Hill. He reached for his cellphone on those sleepless nights and flooded the tiny room with artificial light. There it appeared, the Crimson Cross 8” x 31.5” preassembled skateboard moving in an unbroken line across America headed straight for Frank Catalano, fresh divorcé.

He sliced through the packing tape when it finally arrived, raising the board high above his head like something holy. As a teen at the turn of the millennium, Frank had goofed around with skateboards like the rest of his athletic friends, would clip a Discman to his jeans and sail across those inky black parking lots. Even then he couldn’t compare to the best skaters of Central Catholic, kids who effortlessly grinded rails and impressed the girls who smelled permanently of patchouli. Frank was captain of the hockey team and occasionally landed a successful kickflip while his best friend Rocco hooted from the trunk of his car.

So it wasn’t nostalgia that summoned Frank back to skateboarding, but something more difficult to convey. He’d deleted most of his social media accounts after the divorce. He knew what he’d find there and couldn’t bear scrolling past Amy mugging in her new house or posing with her brand-new hybrid car. But Frank held onto Instagram because he never uploaded pictures and hadn’t added a single friend. Instead, he went by the anonymous BlackAndGold1984_Guy and confined himself to the discover tab and its surprising number of hockey reels. Each time he liked a video of some rando landing a trick shot, the algorithm would remember and beam related topics his way. This eventually led him to skateboarding and the many reels of daredevils attempting goofy-foot nollies over car-sized gaps. He had no illusions about leaping gaps himself. Pickup games at the Ice Complex kept him in shape, but he was still a thirty-six-year-old man who drank a case of Yuengling every week. But if he could just skateboard again and balance the weight of his body on that wooden board for even a handful minutes, then he could definitively prove to himself that he was headed in the right direction and not a fool for nurturing hope for the future.

Frank tucked the new skateboard under his arm and climbed into his sedan, a Saturn with a quarter-million miles on the odometer. The art under the board depicted a bloody cross guarded by ghosts. Nothing macabre. Just some ragtag Caspers like kids on Halloween wearing bedsheets with their eyes cut out. He’d chosen this board on impulse, grateful for that familiar rush of endorphins, the chemical happiness produced whenever he “did a capitalism” like his Gen Z coworkers teased. Frank zipper merged onto the highway and drove to the suburbs, steering into a boarded-up strip mall.

Thanks to a dozen how-to videos on YouTube, Frank knew exactly how to position himself on the board above the smooth pavement, how to lead with his right foot and push off with his left, how to swivel his sneakers in the proper direction. All this was muscle memory, and Frank felt deeply reassured by how easily it returned, how quickly he picked up speed and carved circles just by crouching and leaning slightly to the left. Skating made him feel like a tiny bird had hatched inside his body, a delicate secret that flushed his cheeks. Frank couldn’t kickflip or ollie or grind, but he could at least propel himself forward. That, more than anything else, was something worth living for.

#

Frank sprained his ankle two weeks later, but what a glorious period it was. What he loved most about his new life as a skateboarder was how dramatically it transformed his worldview. Before skateboarding, Frank drove to work on autopilot, zoning out to hockey podcasts or talk radio. Mondays through Thursdays, Frank was as an office temp for a shipping company in the suburbs. But since that was only part-time, he also picked up hours at Trader Joe’s, tearing open cartons of orange chicken or palak paneer, working just long enough for the benefits. He rarely noticed his surroundings because he’d lived in Pittsburgh all his life and knew its bridges and curves as intimately as the topography of Amy’s body. But as a skateboarder, he found himself noting every empty lot he passed. This wasn’t blight; it was opportunity! Skateboarding filtered his reality, and patches of Pittsburgh he’d never truly noticed before—a sloping set of rails off Park Avenue, the curved ledges by the post office—pulsed alive with wonder and possibility. During those magical two weeks, Frank rode every day. He even bought a pair of Nike Blazers popular on r/Skateboarding and admired his transformation in his bedroom mirror, how powerful he now appeared.

Frank knew from Reddit that everyone fell and that it was better to get it over with. But after his initial success, he tricked himself into believing that he was perhaps the exception, a former athlete with unusual control over his body. It wouldn’t have been so bad if he fell doing something cool. But instead, he was skating very slowly through a Dollar Tree parking lot when he attempted to kick turn around a patch of gravel. The board shot out from under his Blazers, and Frank’s right foot buckled at a ninety-degree angle. He fell gently to the ground and assumed everything was fine, that he’d crossed the harmless threshold he read about online. But after standing, Frank discovered he couldn’t feel his right foot, stiff as board. It was evening in August, and the breeze gave Frank gooseflesh, a preview of the autumn to come.

Frank managed the short drive home and undid his Blazers at the door. A softball-sized lump emerged from his ankle sock, and Frank just stared at it, checking his watch to see when his mother would return from Mineo’s. In high school, he’d fallen dozens of times on his cheapo skateboard from K-Mart and popped right back up like a spring. During hockey games, he must have collapsed against the unforgiving ice a hundred times and not once did he suffer an injury! How had this happened when he was skating so slowly, barely doing anything, barely even moving? He typed “swollen ankle” into his phone and elevated his leg in his father’s old armchair, icing the sprain with a bag of frozen peas.

His mother found him there hours later. She listlessly said hello from the doorway, undoing her discount sneakers and setting them next to his Blazers. But when she noticed her son pressing frozen peas to his ankle, she raised her hand to her lips and asked, “What happened, Frankie? Show me.”

Frank had dreaded this moment all evening but didn’t see any way around it. He removed the peas, revealing the softball-shaped bulge as large and distressing as before, not black and blue or even purple, but white like a perfectly formed snowball.

“You’re thirty-six years old and fooling around with skateboards! Mamma-draga, Mamma-draga.”

If Frank had even a tiny bit more energy, he would’ve rolled his eyes. All his life his mother had invoked “Mamma-draga” after every misfortune—from the Steelers losing the opening coin toss to when she called Frankie explaining that his father had suffered a heart attack while driving. She’d discovered Mamma-draga through her grandfather, a butcher in the Strip District who emigrated from a small mountain town in Sicily. Nonno Nicola captivated Frank’s mother with harrowing tales of Mamma-draga, the Sicilian ogress who terrified the island’s bambini. According to him, Mamma-draga lived in a subterranean realm connected to the surface through a magical portal at the bottom of every trash bin in Sicily! All day and all night, Mamma-draga lurked, waiting for some unsuspecting child to loot around the trash, and only then would she pounce, luring the fool below with tales of gelo di melone. If a child was a well-behaved Catholic who had recently confessed their sins to the priest, Mamma-draga made good on her promises, and the bambino returned to the surface fruit-drunk and draped in the finest silks. But if the child hadn’t confessed, Mamma-draga consumed the nasty child whole, savoring its blood the way Nonno Nicola relished his nightly glass of Chianti, the ogress decorating the underground with the shattered bones of dead children.

Frank had heard enough about Mamma-draga to last a lifetime, yet even now the ogress held power over him. His mother described Mamma-draga as a hulking grandmother with stringy white hair, and Frank still imagined her luring Pittsburgh’s wicked into the underground of Sicilian legend, down through the city’s trash. When his father died, that’s where he pictured him—hung up on a chain dragged by Mamma-draga through a cave. Even after months and months of trying, that’s where he imagined his unblossomed children—sealed away in the ruined world below.

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the publisher and should not be reprinted without permission. Author photo credit: Theresa Beckheusen.