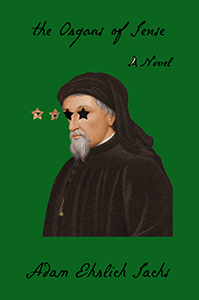

“This book is only for people who like joy, absurdity, passion, genius, dry wit, youthful folly, amusing historical arcana, or telescopes.” —Rivka Galchen, author of Little Labors and American Innovations

“Sachs’s stories… feel like Saturday Night Live sketches written by Kafka. Each is poignant and absurd, and all are told with an exceedingly light touch that floats, skips, and hops into a punch line. Don’t miss out on this one.” —Matthew Zeitlin, Buzzfeed

From the publisher: “In 1666, an astronomer makes a prediction shared by no one else in the world: at the stroke of noon on June 30 of that year, a solar eclipse will cast all of Europe into total darkness for four seconds. This astronomer is rumored to be using the longest telescope ever built, but he is also known to be blind—and not only blind, but incapable of sight, both his eyes having been plucked out some time before under mysterious circumstances. Is he mad? Or does he, despite this impairment, have an insight denied the other scholars of his day?

These questions intrigue the young Gottfried Leibniz—not yet the world-renowned polymath who would go on to discover calculus, but a nineteen-year-old whose faith in reason is shaky at best. Leibniz sets off to investigate the astronomer’s claim, and over the three hours remaining before the eclipse occurs—or fails to occur—the astronomer tells the scholar the haunting and hilarious story behind his strange prediction: a tale that ends up encompassing kings and princes, family squabbles, obsessive pursuits, insanity, philosophy, art, loss, and the horrors of war.

Written with a tip of the hat to the works of Thomas Bernhard and Franz Kafka, The Organs of Sense stands as a towering comic fable: a story about the nature of perception, and the ways the heart of a loved one can prove as unfathomable as the stars.”

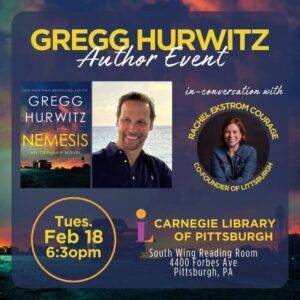

About the author: “Adam Ehrlich Sachs is the author of the collection Inherited Disorders: Stories, Parables, and Problems, which was a semifinalist for the Thurber Prize for American Humor and a finalist for the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, and n+1, among other publications, and he was named a 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow. He has a degree in the history of science from Harvard, where he was a member of The Harvard Lampoon, and currently lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.”

Don’t miss out: Adam Ehrlich Sachs will be speaking at Pittsburgh Arts and Lectures on May 30th!

The astral tube, which others call the telescope, was invented not, as is commonly claimed, in 1608, but in 1599, according to the astronomer, by which Leibniz notes he presumably meant 1604, nor was it invented by a Dutch spectacle-maker, nor by a Florentine mathematician, nor again by a Neapolitan magus, to which figures history conspires to give credit because it does not want to admit that the person who first extended one of man’s senses was merely the self-taught son of a Prague sculptor. The astronomer had penetrated the secrets of nature on his own, outside of any institution, e.g., the spectacle-maker guilds, the mathematical faculties, the esoteric circles of magi, and for that reason history had always been suspicious of him and had always conspired against him. “Yet this tube is no more Galileo’s tube than that star is Kepler’s star, and this I shall prove to you, Herr Leibniz,” he said. “You asked how I lost my eyes, and you asked how I can see without my eyes, but you failed to ask, How did you discover your tube? If wisdom consists, as the saying goes, in asking the right questions, it would have been wiser to ask not only the two eye questions but also the one tube question. Yet you shall know the answer to all three before the eclipse plunges us into darkness.

The astral tube, which others call the telescope, was invented not, as is commonly claimed, in 1608, but in 1599, according to the astronomer, by which Leibniz notes he presumably meant 1604, nor was it invented by a Dutch spectacle-maker, nor by a Florentine mathematician, nor again by a Neapolitan magus, to which figures history conspires to give credit because it does not want to admit that the person who first extended one of man’s senses was merely the self-taught son of a Prague sculptor. The astronomer had penetrated the secrets of nature on his own, outside of any institution, e.g., the spectacle-maker guilds, the mathematical faculties, the esoteric circles of magi, and for that reason history had always been suspicious of him and had always conspired against him. “Yet this tube is no more Galileo’s tube than that star is Kepler’s star, and this I shall prove to you, Herr Leibniz,” he said. “You asked how I lost my eyes, and you asked how I can see without my eyes, but you failed to ask, How did you discover your tube? If wisdom consists, as the saying goes, in asking the right questions, it would have been wiser to ask not only the two eye questions but also the one tube question. Yet you shall know the answer to all three before the eclipse plunges us into darkness.

“And at the moment we are plunged into darkness, you shall see that these three questions are really one question,” he added, peering into the telescope, picking up his quill, and writing something down—a long string of numbers, or so it seemed to Leibniz in the faint flickering candlelight.

“And at the moment we are plunged into darkness, you shall see that these three questions are really one question,” he added, peering into the telescope, picking up his quill, and writing something down—a long string of numbers, or so it seemed to Leibniz in the faint flickering candlelight.

“You because you’re still young probably believe that the things you invent and the things you discover will be named after you, whereas the things invented by others and the things discovered by others will be named after others. It is not so. For example, I had nothing whatsoever to do with a certain mechanism for the very rapid and ostensibly painless plucking of feathers from a duck. And yet it is named after me. There is a contraption for hoisting the curtains of a theater with the press of a pedal not the crank of a winch—I’ve never touched it! But of course they attribute that curtain contraption to me. I did not discover the rodent that bears my name. There is in the Americas a fungus . . . in short, I have never laid eyes on that fungus. And so on. Yet the telescope, which is mine, they give to others.”

Then the astronomer said: “Of course, whether the telescope is attributed to me or someone else doesn’t really matter, I’m even a little bit ashamed to harp on it, because when I die, which by my calculations will happen not long after the eclipse that will take place some two and three-quarters hours from now, I will be taking the telescope with me, and I will be taking Galileo and Kepler with me, and I’ll be taking Tycho with me, too, they’re all dead of course but nevertheless I’ll be taking them all with me, and anyone who credits the telescope to anyone else I’ll be taking with me, as well as the people they credit, as well as everyone else, and actually I’ll be taking the whole world with me, and even you, Herr Leibniz, I will be taking you with me, too, you probably didn’t know that! You because you’re young probably think that you’ll take the world with you when you die, deep down every young person thinks that he will take the world with him when he dies, that’s the canonical young person’s belief, because deep down young people don’t really believe in the reality of other people, they haven’t had the sheer reality of other people drummed into them yet by the schools, but what I have discovered through the most rigorous astronomical research is that I will actually take the world with me when I die. As a child I stupidly believed that I would take the world with me when I died, which belief was fortunately drummed out of me during the few years of schooling I had before my father whisked me into his workshop. The reality of other people was drummed into me and my belief that I would take the world with me when I died was accordingly drummed out of me. I learned next to nothing in school, but the sheer reality of other people was drummed into me. Elementary school is mostly useless, of course, but as a social mechanism for drumming into people the sheer reality of other people it is probably unsurpassed. I’m actually grateful for school, because by the time my father yanked me out of it by the ears I genuinely believed in the sheer reality of other people! Which, needless to say, is an extremely useful belief for going about life. There’s no more practical belief for going about life, and through life, than a belief in the reality of other people. Almost no one succeeds in the world without that belief, and all art and science flows out of that extremely expedient and uniquely advantageous belief, without which the stock market, too, would actually immediately shut down. And as a consequence of that belief being drummed into me, my childish, self-indulgent belief that I would take the world with me when I died was, thankfully, drummed out of me. Of course I eventually found my way back to that belief and realized it was perfectly true, but now it was true for the most rigorous and quantitative astronomical reasons,” the astronomer said, patting the telescope. “Every great thinker, by the way, has always without exception found his way back to his earliest childhood beliefs; right at the end he realizes that his whole intellectual life has been nothing more than a putting-on-firm-foundations of what he thought right at the start. Bad thinkers, I include incidentally Kepler and Tycho and Galileo in this category, and also Copernicus, start over here and end up over there, and the farther apart here and there are the better they think they’ve thought, and the louder the world claps, as if they’re children in a jumping competition, because the world thinks thinking is a kind of jumping, and in fact the kind of thinking Kepler did was a kind of jumping, but true thinking is actually an elaborate standing-still, or at most a going-over-there followed by a coming-back-here. While the world applauds the thinkers who choose to participate in the children’s jumping competition, the true thinkers are standing utterly still in a very complicated way. And since nonthinkers also tend to stand quite still, and nonthinkers vastly outnumber true thinkers, the world assumes that anyone standing still is a nonthinker and therefore does not applaud these standing-still types; but if you look very closely at a nonthinker and a true thinker you’ll notice that they’re actually standing still in completely different ways. So I came to realize that I really would take the world with me when I died, the fixed stars and the erratic ones and the Earth and the Sun and everything else, just as I had once thought, I would, not you, and not anyone else, either, but for entirely different reasons than I had once thought,” the astronomer said, patting the telescope. The content of the belief was the same but the armature around it and supporting it from underneath had gone from “pure childishness” to “extreme scientificity.”

“This probably sounds obscure but what I mean will become perfectly clear,” the astronomer told Leibniz. He pressed an empty socket to his telescope, picked up his quill, and wrote down a long string of numbers.

Since this belief turned out to be true, it didn’t matter, according to the astronomer, who got credit for inventing the telescope, it was petty and absurd to go on and on about the credit he deserved but did not get, he said. Who cares! Let Galileo have credit, or Lipperhey, or Kepler, or Della Porta, or whomever else, “Seriously, who cares?” cried the astronomer. Who cares! Who cares! Who cares! Who cares! Still, it was slightly better, he supposed, for the last two-odd hours of the world to possess a smidgen more truth and a smidgen less falsity, and, in any case, the young man had asked what happened to his eyes, and how he could see the firmament without them, questions that were of course intimately connected to the question of the development of the telescope, which was of course a variant of the question of who truly invented the telescope, i.e., me, the astronomer said, these three questions are really one question, so here, he said, in Leibniz’s written account, is the fact of the matter.

Excerpted from THE ORGANS OF SENSE by Adam Ehrlich Sachs. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux May 21st 2019. Copyright © 2019 by Adam Ehrlich Sachs. All rights reserved.