From the Publisher: “Always a big-hearted and gritty chronicler of the lives literature often forgets—truck-stop waitresses and mill workers, fathers and mothers struggling to afford shoes for their kids—poet and novelist Newman makes the move to nonfiction in his latest book, The Same Dead Songs: a memoir of working-class addictions (Imperfect Union / J. New Books Winter), telling the story of Anthony, a man struggling with addiction, unemployment, and crime.

Anthony and Newman grew up in the same Western Pennsylvania neighborhood. Newman—having recently lost his job teaching college—is in his late 30s, a devoted father, brother, and husband. He’s also a newly published novelist, desperate to keep writing in a world that dismisses working-class literature.

Anthony is in his early 40s, deep into his struggles with gambling, booze, and hard drugs.

Anthony is an addict. Newman is someone who likes to drink and sometimes uses drugs. As Newman tries to maintain a stable life, Anthony binges then repeatedly shows up on Newman’s doorstep, looking for help or a place to get drunk or both. The drugs, booze, and intimacy bring back memories of growing up and the roughness of their shared experiences. One wants to build a better life and help a friend. The other rejects anything resembling help.

‘The ghosts of childhood and geography and the working-class bind us like nails in boards, like drink in a glass,’ Newman writes, ‘or they do not bind us at all.'”

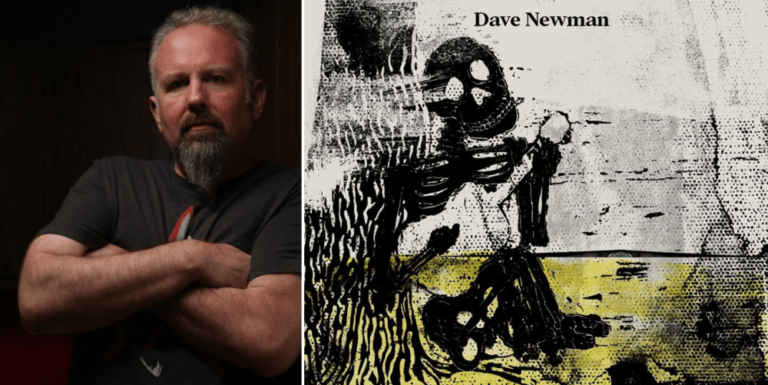

More info About the Author: “Dave Newman is the author of seven books, including The Same Dead Songs: a memoir of working-class addictions(Imperfect Union, Winter 2022) and East Pittsburgh Downlow (J.New Books, 2019). His collection The Slaughterhouse Poems (White Gorilla Press, 2013) was named one of the best books of the year by L Magazine. His poems, essays, and stories have appeared in magazines around the world. He appeared in the PBS documentary narrated by Rick Sebak about Pittsburgh writers. Winner of numerous awards, including the Andre Dubus Novella Prize, he lives in Trafford, PA, the last town in the Electric Valley, with his wife, the writer Lori Jakiela, and their two children. After a decade of working in medical research, he currently teaches in the Creative and Professional Writing Program at The University of Pittsburgh-Greensburg. For more, visit his Facebook/Meta page here.”

Newman on Facebook “‘If you’re working class, you understand that no one understands you.’ Dave Newman’s fierce and jittery memoir reveals, in un-sanitized detail and naked, smart reflection, the story of a working-class casualty–or near casualty–that a less honest, less inquisitive writer might avoid. In this exquisitely paced, wrenchingly beautiful tale of addictions, of needing help, of helping and not helping, of fighting and surviving, of the will and wonder and work of loving hard, of brokenness and the precarious impulse to apply the glue and clamp ourselves back together, Newman proves that he is beyond truth-seeker. He is a truth be-er. The Same Dead Songs is a darkly enjoyable, heart-opening schooling.” –Nancy Krygowski, award-winning author of The Woman in the Corner

“There are writers who understand America and there are writers who understand an America most writers don’t write about. This short-money, low-end, no expectations, working-class, just-skating-by America is the one Dave Newman lays bare in achingly beautiful, badass, and authentic prose… Readers will hear echoes of Raymond Carver, Daniel Woodrell and Denis Johnson, but in the end, Newman has earned a place of his own in the pantheon.” –Jerry Stahl, bestselling author of Permanent Midnight

“Dave Newman is an immense talent!” –Donald Ray Pollock, author of The Devil All the Time and Knockemstiff

“Finally a writer who tells the stark truth: most scribes make the same wages as busboys, curse like truckers, and drink like—well—writers. Dave Newman’s characters are real people, not ideas with arms and legs.” –Larry Fondation, author of Fish, Soap and Bonds

PUNCHING ANTHONY (Excerpt from THE SAME DEAD SONGS)

I punched Anthony around the same time, a little later, right after I graduated from high school. I broke my hand on his face then had to beat his head off the asphalt to get him to stop swinging at me, to get him to stop swinging at everyone.

I punched Anthony around the same time, a little later, right after I graduated from high school. I broke my hand on his face then had to beat his head off the asphalt to get him to stop swinging at me, to get him to stop swinging at everyone.

We’d been drinking at a bachelor party for a neighborhood guy, one of Anthony’s and my brother’s best friends, a guy getting married right out of college. A guy nicknamed Mud. You don’t need to remember his name but what a sweetie. The bachelor party started at a local bar where my brother had reserved the back room. A few dads were there. Everyone dressed nice. I wore a sleeveless sweater with a white t-shirt underneath, khaki shorts, and dockside shoes. All bought at TJ Maxx or Gabriel Brothers or some discount store with money I’d earned working at a paint store. The night was not meant to be a rowdy time. No one mentioned strippers or prostitutes or rum drinks or whatever men did at bachelor parties in movies. None of us had ever attended a bachelor party or thrown one. This was more like friends celebrating, more like friends trying on adulthood, preparing themselves for the coming years. The bachelor had been hired on at the school where he’d student taught. Everyone else still worked shit jobs while looking for careers. I’d yet to start college. I’d yet to imagine anything beyond the moment. But we were all happy that the bachelor had a job. We all dreamed the same.

One of the guys at the party came from a family that owned a chain of grocery stores in central Pennsylvania. I’d met him once while visiting my brother at college. He seemed like a sweet dude. Easy to talk with. A good listener. He’d been impressed by how fast I could chug a beer. I appreciated the attention. I asked about the grocery stores because owning grocery stores seemed impressive, like being a rockstar or putting a jacuzzi on your porch. He told me what he did when he headed home on weekends and it sounded like he worked in a grocery store, not owned one. Stock. Cash register. Trash. I liked him more because of the tasks.

On the night of the bachelor party he looked like everyone else in the backroom of a dive bar in a little town outside of Pittsburgh—same clothes, same hair, same pizza belly all the recent graduates sported. Even his car parked outside was a slug.

We hugged when he arrived then I went back to drinking with old pals while he blended in with the rest of the room. I barely noticed what he did or who he talked to.

Anthony noticed him a lot.

The more Anthony drank, the more he thought about a family owning grocery stores, more than one, a chain for fuck’s sake, and a young man with a degree from a very average state school inheriting a million dollars’ worth of sellable food and underpaid employees.

Anthony knew, somehow, the employees were underpaid.

Most of us in the room knew people who worked for large corporations like Volkswagen or US Steel, doing labor or a skilled trade. The bachelor’s dad worked for Westinghouse as a machinist. Anthony’s dad drove cross-country truck. Another guy, a guy just out of the Navy, worked with his dad for a tree-cutting business. His dad had shot a man who had either broken into their house or was sneaking in to fuck his wife.

That’s another essay.

These stories spin and grow.

But I thought owning something was impressive.

Or I thought nothing about it at all.

None of us knew anything more than the tiny world we spun.

My brother walked by and, for fun, kissed me on the forehead.

I was so happy he was my brother.

I was so so happy he was my brother.

I wanted to be around him always.

The bachelor party continued, adventure without the downside.

Then the continuation stopped.

Before Anthony singled out the grocery store guy, before he started mocking him and saying, “Hey Mr. Produce Man,” and sneering like he wanted to make his mouth a gun, he picked up a full bottle of whiskey—unopened and gifted to the groom—wound up like he was trying to throw a fastball, then smashed it off the back wall of the bar.

I watched it, knowing it would happen, hoping it wouldn’t happen.

Now step back seven seconds.

The evening sun was out, shining bright every time the bar door opened.

Old friends met new friends.

Old adults chatted with young adults.

Occasional toasts were made to the groom, all sweet, nothing long.

We were men too young to know what a celebration was but wanted to celebrate.

The old guys were old guys.

I was happy to be in a bar.

I was underaged.

I was happy we all could afford to be in a bar.

My poor brother, not even remotely established, not even knowing what established meant, probably worrying about his deposit, the money he’d put down to reserve this place, but trying not to worry, trying to make his old pal the bachelor happy, drank and socialized like he knew he’d be okay in the future and not always live as a confused graduate begging for a job in his field if he even knew what his field was which he did not.

Then an epic smash.

+ + +

Few things interrupt a dream like broken glass.

We all stood in silence, little wrecking balls of sadness and hope quietly knocking the inside of our skulls until we understood this was not a bachelor party but a demolition.

I scanned the room and found my brother.

My brother looked at Anthony like he’d arrived from Jupiter with a ring made of ice he wanted to crack into cubes, like Anthony could travel great distances and return with destruction, an alien invasion made of friendship and everything worse.

Why and what the fuck and again and please don’t.

Anthony leaned against the wall like he might collapse then turned to all of us, wild-eyed and furious, and breathed deep like he’d been drowning in an ocean and now found oxygen.

I hoped it might be over.

I hoped we might pretend this was an accident.

I just wanted to get drunk and talk with friends.

My brother stepped to Anthony then stopped.

A second passed like a decade.

Anthony quit looking at us and contorted his body like he’d been broken and repaired then broken again. Then he howled, deep and loud and long, his arms reaching straight down at his sides like he wanted to dig a grave with his fists while he stretched out his neck and reached for the ceiling with his mouth and whatever guttural sound he shouted out.

Someone said, “What the fuck, Anth?”

One of the dads started picking up the broken glass from the whiskey puddle. I was underaged and scared to get outted for being a teenager, scared that someone would call the cops. I’d already spent a night in jail for being underaged in a strip bar. I hated being arrested. I hated getting punched in the neck with a cop flashlight.

Everyone pointed their eyes away from Anthony and whispered.

The end seemed near but it was not.

Fucking Anthony, I thought.

No one else was within four years of my age.

I squatted down and helped with the broken glass.

A backroom in a dive bar is a special place, almost safe, maybe safe, then not safe at all. I listened for sirens. The whiskey smelled like broken old men and baseball coaches. It smelled like closed factories and welfare. I wanted to be useful. I’ve always wanted to be useful. I was exhausted from finishing high school without my dad around, from dealing with my mom and her stress over selling the house and moving to Michigan. I was exhausted and crushed over a break-up with my girlfriend. I worried about money, about student loans. Then the strip club and jail. Fines and charges were imminent. I knew I was fucked. I knew I’d fucked myself.

Pause and move on.

We started up again without much complaint, offering a collective sigh over the broken whiskey bottle but hoping for more friendship and celebration. More drinking. More weirdness. Happy weirdness. More memories about the bachelor. More toasts. More kind comments. Aside from Anthony cracking wise about grocery store owners, which everyone pretended was not a thing, time turned itself into a party we all wanted to dance at. I drank. Everyone drank. Music played. Everyone talked. Strangers became pals. The bachelor ate a bag of chips. He looked hammered and happy. He was deeply in love with his wife and would have rather been there, with her, away from his pals. Meaning adulthood. I’m just guessing. I stayed clear of Anthony. Others engaged him. I hope they made him feel loved.

The dads waved and smiled and headed home.

+ + +

Eventually, we ended up in a room at Conley’s Motor Inn in Irwin, right on Route 30, one of the great American highways. It was a fuck motel that had been there for decades, a row of boxes advertising itself as rooms with a bar and an indoor pool. Eventually, it’d become a place advertising itself as a birthday party destination for small children who wanted to swim before they ate cake. When that failed, it became a huge storage unit.

It’s a huge storage unit now.

The shape of the building and the parking lot remain.

I can’t remember how many of us where in the room.

I guess a lot.

Some folks, the ones not interested in drinking or not very good at it, wished the bachelor the best and promised to see him at his wedding and headed home. Anthony existed in everyone’s thoughts so we pretended he did not. His violence was a tree growing over us but so was the world. I come from a culture that blames themselves for everything. We knew Anthony was us and a mess. Sorry. None of us could have articulated our struggles, our families’ struggles, our neighbors’ struggles. We thought we were guilty for being alive because no one wanted us. Eventually, I started reading books and wanted to try. I’m writing for a space where I can pay my bills and breathe and tell the truth.

I’m sure you are too.

I’m sure you are too, reader who needs a better job.

Beer in a cooler sat in a corner of the motel room. I held a wet can in my hand. My broke-ass brother probably bought the beer and the cooler on his credit card, one of his almost-filled credit cards. What a good person he was and is. We all stood together.

The room was too small.

Two beds, one bathroom. Poor lighting. Unfluffed pillows. Flowered comforters made of death and bad sex and combustible thread. I pissed and washed my hands with a sliver of soap made of adultery and maids who hated to clean because they were underpaid. I hoped the night would sail to morning with success.

I ignored the chick talk.

I thought about my ex-girlfriend and told myself not to call her.

If I called her, I knew she’d never come back to me.

She was so smart and pretty but moving on.

The number of us in the room continued to shrink.

Some guys sat on chairs, some sat on the bed.

We tried to party, whatever that meant.

The energy felt like stabbing, a knifing.

A lot of goofy and mean and awful shit happened, meaning jokes and touches and whatever else the world does to show working folks we can’t get along while trying to get along.

Everyone kept drinking and being polite.

I come from a culture that blames themselves for everything.

I said that already.

We knew the strange that was about to happen.

Then Anthony escalated everything.

Find a dude that hates himself and it will happen.

Everyone tried to calm it down.

My brother said, “Anthony, chill.”

Anthony did not chill.

He kept on, saying, “You think you’re better than us, Mr. Produce Man?”

I mean, a thousand times, relentless.

The guy who owned the grocery stores crumbled in shame, apologizing, apologizing without knowing what he was apologizing for.

Finally, Anthony jumped on him.

It was like lightning coming from dirt.

Anthony held the guy on the bed and sort of strangled his body in a pathetic way.

I tried to pull Anthony off.

I pulled him off.

I was young and strong.

Anthony stood, pushing his fury at me.

I said, “Settle down.”

Energy passed between us without definition.

Then I threw him into a wall.

He hit the wall and settled then said, “Fucking nice.”

He thought I was fucking him.

He believed he wasn’t fucking anyone.

The grocery store guy, not used to violence, not used to being confronted, not used to socialism or maniacs, but used to parties without consequence, used to civility, used to evenings without degradation, turned and said, “What just happened?” while adjusting his shirt, while adjusting his pants, while un-disheveling himself, and looking like he might cry or fall down or erase history, his and ours, then he pulled his hair like a wish list.

If you’re working class, you understand that no one understands you.

If you’re working class, you understand your limits, which are not your limits, which are the world’s limits, that everyone you meet thinks you’re limited.

The guy whose family owned grocery stores looked like he might never speak to his working-class pals again. He looked like a king, royalty who escaped a sword.

He looked like he might turn his family’s grocery store into a graveyard and live there.

The muscles in the room looked like knives.

My brother cleared the room so he could calm Anthony down.

My brother stood up to the present, meaning all our futures.

“Out,” he said.

He said, “Everyone out.”

The calm passed through us like calm, like unexpected calm.

We all left, thinking we’d completed something and could start again.

We walked through the weird hallways of a fuck motel and across bad carpet and bumped into walls that needed painted and found an exit and ended up outside. We all stood around in the parking lot, confused on asphalt, near a highway we’d grown up on and hadn’t considered. The general consensus was: what the fuck.

And it still is.

I am as close to my brother now, thirty years later, as I was to him then, maybe more if that is even possible, and we have told this story so many times with laughter and pain and embarrassment and mostly laughter, but he never mentions what he said to Anthony while the rest of us huddled in the parking lot of a dive motel without an understanding of why a friend would ruin something made by and for friends.

It wasn’t a secret why Anthony flipped out.

He flipped out because he was flippable.

The life he dreamed without knowing he’d dream a life was of failure.

The future looked like broken glass and spit.

I assumed it was all of our futures.

One of my pals, a neighbor, Lester, said, “What the fuck is wrong with Anthony?”

That seem obvious.

Lester held soul and truth. He’d grown up with a dad with a broken spine, a man who wanted to work and provide and ended up drunk because no one wanted him to work and provide because his back was made of surgery. His mom worked as a janitor. She pushed a broom and cared for everyone, her kids, the kids in the neighborhood. She made hot sausage in a crockpot and we showed up and ate. Lester knew the pain of money and struggle. I loved him. I love him still, the guy I grew up with, the guy who works with intellectually disabled kids.

We stood in a parking lot of a shit motel.

He said, again, “What the fuck is wrong with Anthony?”

I lacked words.

I wondered if something was wrong with me.

Then Anthony sprinted from the motel, shirtless and furious.

He came at me like a car.

Lester said, “Kick his fucking ass.”

Lester, my childhood pal and saint.

His dad worked the railroad then broke his back. His mom worked as a janitor in a local high school. I said that. I loved their house, that they had an aboveground pool. Everything revolved around the neighborhood, how friends could be friends and make each other better.

I trusted Lester.

Anthony flamed on.

That’s when the fighting started in the parking lot.

Later, the doctor inserted a metal rod into my hand, starting below the pinkie on my right hand down into one of the carpal bones, probably the hamate. After six weeks she removed the cast and it hurt like hell when she pulled out the pin with what appeared to be needle-nose pliers, saying, with disgust, “You did this to yourself.”

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and publisher and should not be reprinted without permission.