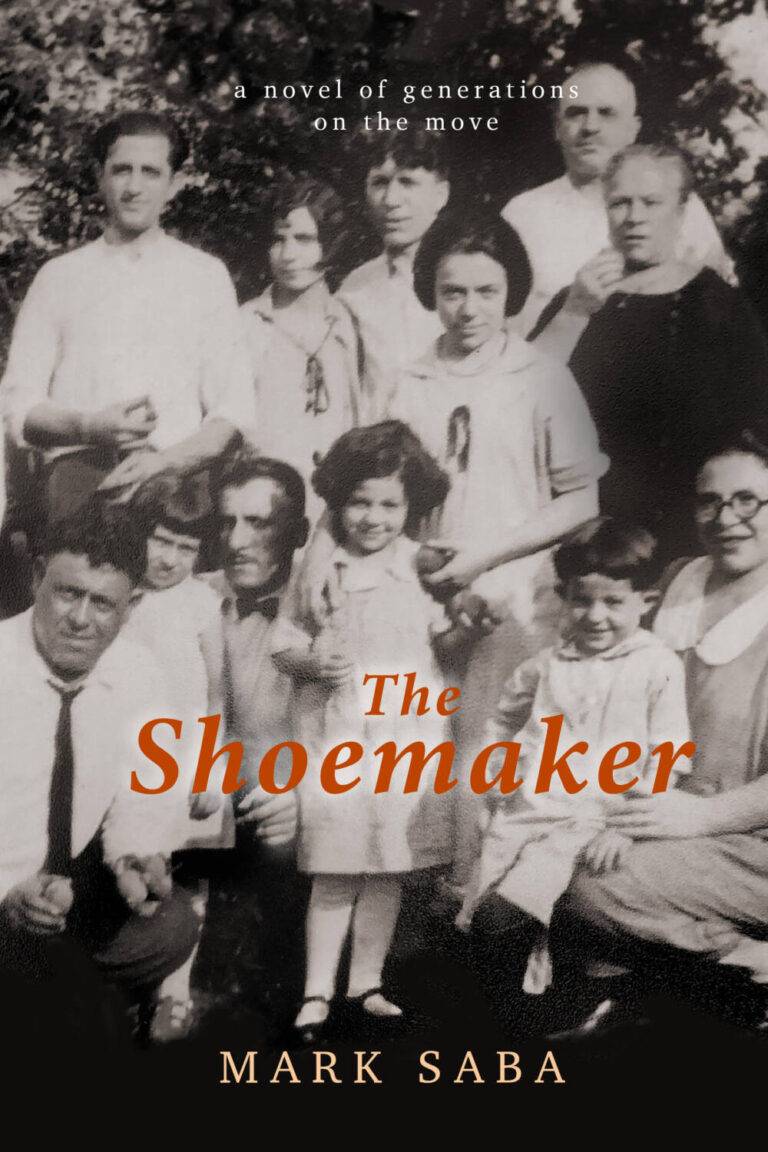

“A beautiful, poetic, ethereal read, The Shoemaker is the story of a great-grandfather and great-grandson connected by blood and by their passion for shoes. At first Manny has little time for his ancestors, but as his great-grandfather’s life draws magically closer, at times aided by benevolent apparitions, he begins to glimpse the answers to the questions about the meaning of life that have been plaguing him. Shoes play an important and enlightening role throughout the story and deliver so many gems I had to stop and savor, my favorite being that with a good pair of shoes, you can go anywhere and achieve anything. Masterfully told, the further you read, the tighter the threads the author has so expertly woven come together, leaving you, like Manny, with a renewed perspective of the meaning of family, home, and what to do with our precious time on this earth.” —Hilary Hauck, author of From Ashes to Song and The Things We’ll Never Have

More info About the Author: Mark Saba grew up in Pittsburgh of Italian and Polish heritage. He is the author of poetry books (Calling the Names, Painting a Disappearing Canvas and Flowers in the Dark) as well as the fiction titles A Luke of All Ages/Fire and Ice (novellas) and Ghost Tracks: Stories of Pittsburgh Past. His poetry, fiction, and nonfiction have appeared widely in literary magazines and anthologies as well. Also a visual artist, he paints and produces poetry videos. Recently he retired from his position as medical illustrator and graphic designer at Yale University. He and his wife now live in Maine.

Author Site

From a hilltop that overlooked other hills east of the city, as well as the valleys of two opposing rivers, they gathered to mourn the death of their father, Pietro Cavalieri. The youngest stayed well behind their black-clad elders, leaving the business of grieving to them, who bore that responsibility almost wholly for their beloved matriarch, Almerinda Marchionna-Cavalieri. For privately they believed the old man to be a son-of-a-bitch.

“Pete! Pete! Perchè tu m’hai lasciato?” she wailed, asking the heavens once again why, and receiving for an answer only the simple, saddened faces of her progeny. She knew then, finally, that they could never share her grief, because they had not known Pietro in the way she had.

After the old priest had finished his prayers and a strong gust of fall wind had blown his prayer book shut, Pietro felt the first clods fall into the pit and onto his casket. “When I die,” he’d told his wife more than once, “just tie me into a sack and throw me in the river. Don’t waste our money.” It was just one of the many things he’d thrown out to her in a fit of crazed conviction, partly brought on, she’d thought, by the troublesome and unconventional course their lives had taken. She almost always found it in her heart to forgive him, even when he wouldn’t speak to her for weeks at a time. But even that didn’t begin until they had become established in America, in the soot-blackened town that contained every despicable nationality on Earth except the French: the only ones he considered on par with the Italians.

“But Pete, look, we have plenty of food to eat in America, and a promise for our children’s children,” Almerinda would implore. After the expected time-independent scowl he would deign to answer:

“And all we have to do is live here in hell.”

It was customary for them to disagree in silence, for Almerinda knew she was no match for his wit. Often it took a family crisis to get them to speak to one another again. This time, lying in his casket, Pietro did the forgiving. He forgave Almerinda for putting him through this, because he knew now that she did it to honor the family. If he were still alive, he would speak to her; he would tell her this. But it was too late for words. All that he had left her was the words he had already spoken, and the feelings that had left him through his eyes, mouth, and hands on their way to her heart. As the clods of cool Pittsburgh earth fell over him, he gave up contact with the living, and gave up his soul to meet the dead. His last impulse went directly to his beloved Almerinda, who began to tremble from head to toe, while whispering “Addio, Pete—ti sento pian piano come un angelo.” Having spoken these words she regained her composure, stood quietly for a moment, and turned to lead them back down the hill to their cars.

Inside the casket Pietro’s former body lay straight and still, but not perfect—the undertaker had carelessly positioned his tie askew, though no one had dared to straighten it. For that crooked tie, unknown to the funeral home staff, had been Pietro Cavalieri’s trademark; along with an unevenly shaven face, nicked fingers, and a pair of cowlicks that had followed him even into old age, and now into the grave.

During the drive back to the house Almerinda kept her window tightly shut, while her eldest daughter Pina, now forty-eight years old, rolled hers down even further than she would have if her mother hadn’t been in the car.

“Pina, close the window. I feel a draft everywhere today.”

Pina, half lost in her own reverie, virtually ignored Almerinda’s comment until her husband spoke up:

“Pina! Listen to your mother.”

That was a cry she’d heard all too often in her life, and more often than not from her father. She rolled the window up for her babbo, but left it open a slight crack, also for him. He too appreciated fresh air. Almerinda, predicting her daughter’s every move, turned to face her. Pina’s impulse was to stare her down, but finally she succumbed, rolling the window up tightly, while forcing out a sigh that could have sent shivers down a mad dog’s spine. Almerinda wiped her eyes again with her embroidered handkerchief, as Pina felt her heart rising to her throat from having to endure such theatrics.

“Leave her alone,” Pietro warned her. “She’ll work it out. Don’t look at me that way! It’s not my fault I died. Have some respect for your mother. If you are pretty it’s because of her.” It was just like him, thought Pina, to say something like that safely after he’d died.Everyone knew she resembled her father: pointed eyebrows, full eyes, Roman nose, the expressive lips. Her hair was not black but chestnut-colored, and her eyes (though some saw flashes of color in them) gray. She’d never noted the color of her mother’s eyes, but she knew her father’s had been brown—not deep and alluring brown, but brown like the earth and the trees: earth-brown, for he was of the earth. Whatever he was could be read plainly in his eyes. He was the same before everyone, and she was sure now that her father put on no pretense while meeting the Almighty.

This is not to say that she revered him; more than once she had denounced him, either sottovoce or loud enough for her mother to hear. And her mother, beneath that veneer of healthy good looks and generous charm, had eyes of steel. They saw through everything with their clear sky color and endless depth. When Pina heard her full name leaving her mother’s lips, its four hard syllables in somber monotone—Giu-sep-pin-a—she knew the woman was on to something. It was the same tone she used to introduce a serious topic of discussion to her husband: Pi-e-tro. Senti! Pietro rarely listened, and it was Almerinda’s insistence that he should that had annoyed Pina. She was now beginning to feel that things would be different around the house, that Almerinda’s supplications would have to be redirected to someone else. Pina vowed that it would not be her. She was also very good at not listening.

Giuseppina and Jim (he insisted on Anglicizing his non-native-sounding name, Giacomo) had once lived on the second floor of her parents’ house: a modest red-brick, federal style, with a shallow front yard and deeper back, lined on either side by a rusting wire fence against which either tomatoes, zinnias, peppers, or curly endive grew. Pina also harvested their wild dandelions for salad. Almerinda denounced this practice, suggesting that any stray cat or dog might have peed on it. Pina replied instantly: “We ate it always in Italy, don’t you remember?” To which Almerinda snapped: “That was cicoria, not this—” Pina saw no practical difference, and so proceeded unhindered by her mother’s comments, even loading her basket up higher with the bitter greens.

Their house was similar to the majority of houses in this section of east Pittsburgh. Almerinda kept everything about it, inside and out, tidy; Pietro had painted its metal porch awning red and green. The air around it on summer weekends was spiced by the hearty scents of tomato sauce, anise, and cigars. Pietro had proclaimed, during their first year in the house, that it was drafty in winter and baked like an oven in summer. He also cursed all the little things that needed fixing: cabinet doors that stayed ajar, dangling light fixtures, banging radiators. Some tasks he set his sons to finishing; others he entrusted only to himself, quietly enjoying the sudden opportunities to exercise his talent, regardless of what he said.

Pietro was, by trade, a shoemaker. Pina often repeated to her son, after Pietro was gone, that her father had made “a good shoe, not like today.” Pietro consented to having made a good shoe, though he knew deep down that he had once made even better shoes. But, like so many things about his new world, those better shoes would have gone unnoticed. So he said nothing about his shoes, but threw his head back a bit, grimaced, and granted “Eh!” if anyone complimented them. That Pietro considered himself an artisan of the highest caliber was something only he knew, for he preferred not to accept compliments openly, and so eventually everyone stopped giving them. One thing they knew was that if Pietro fixed something it would never break again. What they didn’t know was that he was never satisfied with what he did, and that nothing for him was ever completed until his grandfather’s spirit had come to mark it so. It was a mark only Pietro could see, a mark of near perfection that was only evident on Sunday afternoons or early weekday mornings when the children were still asleep and Almerinda had preoccupied herself with setting the farina to boil.

Pietro’s grandfather, Fiorentino Cavalieri, had also been an artisan. Young Pietro would watch him carefully as he bent hot iron into grillwork for the town’s balconies, gates, and shop signs. Fiorentino had a long white beard, unkempt white hair, and narrow shining eyes.“You learn some trade, Pete. Be sure to, or next thing you know they’ll be sending you to school. There’s already such talk in the North. And whatever happens first in Piemonte will eventually make its way down to the Abruzzi. Listen! Pietro! Find out what your skill is and use it. Practice it. Make them see it before they take you and turn you into a modern imbecile.” After such a little lecture the old Fiorentino would turn his lively eyes back onto his work, leaving Pietro free to hover like an angel about his shop, for Pietro did indeed feel like an angel in his grandfather’s presence: gifted, fated, noted but unnoticed.

In 1880 Pietro turned fifteen. It was to be the most magical year of his life, the year a well ran dry inside him and he felt a lake filling up in its place; the year his childhood left but he was not yet sure of a thing called manhood; the year every sense of his was unlocked, and the world recreated itself daily before him. When he was well past his prime, and fraught with the problems that only the new country could bring, he sometimes looked back on that year, wanting to both relive and forget it, and able to do neither. For it was during that year that he arose at five o’clock to join two friends on an expedition to climb Mount Arazecca. Wearing his grandfather’s hunting boots to protect his legs from the poisonous, ubiquitous vipere that populated his town, and carrying a knapsack filled with sausages, cheese, bread, and wine, he went to meet Pierluigi and Elio on the bridge at the edge of town: the clear water of the Sangro River broke like crystal over its rocks, as trout rose to the surface and flipped their tails into the cool air. When Pietro turned around to face the town he was leaving he saw it in an unfamiliar light; a pale silver that covered every cobblestone, window, chicken, roof tile, and tree. Only one lamp burned far up the old town hill, and he recognized the window it shone through. It belonged to his grandfather’s house.

“Come on, Pete. Hurry! Hurry!”

He turned back and saw that the others had come, already anxious to find the path that led through the brown grass to the foot of Mount Arazecca. They thrashed through the lifting darkness as if being chased, and addressed one another sporadically and succinctly, as if learning a new way of speaking. Together they felt like reinventing everything that morning: the day was about to dawn for them, and they would direct its course, alone, on their manly expedition.

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and publisher and should not be reprinted without permission.

Previously:

Start Reading A Luke of All Ages and Fire and Ice: Two Novellas by Mark Saba…

Start Reading Ghost Tracks: Stories of Pittsburgh Past by Mark Saba…