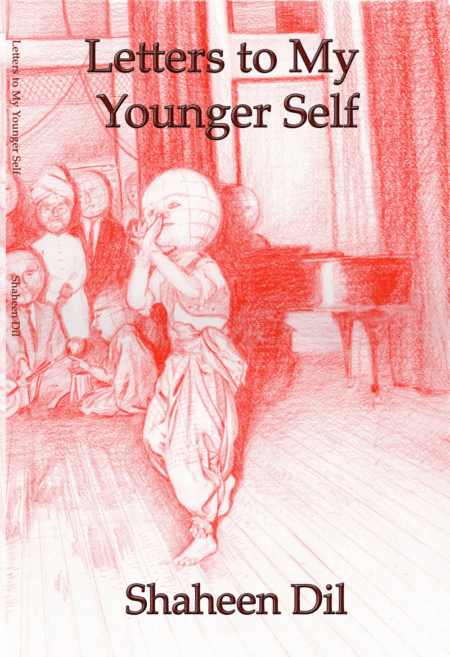

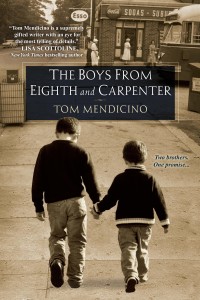

Littsburgh is thrilled to be able to share with you this excerpt from The Boys From Eighth and Carpenter by Tom Mendicino (“a heartfelt story of two loving brothers as well as a compelling crime drama all set in the changing city of Philadelphia”—Lisa Scottoline, New York Times bestselling author). Although The Boys From Eighth… is set in Philly, Mendicino was born and raised in Pittsburgh. This excerpt is published here courtesy of Kensington.

Prologue

giuramento di sangue

April 14, 2008

Promise me you’ll always take care of each other. Frankie, you make sure you tell your brother I asked you both to do that when he’s old enough to understand.

FRANKIE (MORNING THROUGH THE LATE AFTERNOON)

He’s going to the Hair Show just as he’d planned. Frankie Gagliano, proprietor of Gagliano Cuts and Color, Family Owned Since 1928, always goes to the Hair Show. People would notice his absence. But now that he’s sitting in the parking lot, he’s wavering, questioning the wisdom of his decision and lacking the stamina to engage in the usual banter about how quickly time seems to fly and that it’s hard to believe it’s been a year since the last trade show. And, of course, he no sooner picks up his badge than he finds himself face-to-face with Beppe Lopato, his nemesis back at South Philadelphia Beauty Academy, who’s wearing a pair of snug, crotch-grabbing jeans and looking like he subsists on steroids and nutritional supplements. Beppe strikes a pose, giving Frankie a dramatic once-over. Frankie feels the perspiration dripping from his armpits, fearing guilt is written all over his face. Even a Neanderthal like Beppe Lopato can see it.

He’s going to the Hair Show just as he’d planned. Frankie Gagliano, proprietor of Gagliano Cuts and Color, Family Owned Since 1928, always goes to the Hair Show. People would notice his absence. But now that he’s sitting in the parking lot, he’s wavering, questioning the wisdom of his decision and lacking the stamina to engage in the usual banter about how quickly time seems to fly and that it’s hard to believe it’s been a year since the last trade show. And, of course, he no sooner picks up his badge than he finds himself face-to-face with Beppe Lopato, his nemesis back at South Philadelphia Beauty Academy, who’s wearing a pair of snug, crotch-grabbing jeans and looking like he subsists on steroids and nutritional supplements. Beppe strikes a pose, giving Frankie a dramatic once-over. Frankie feels the perspiration dripping from his armpits, fearing guilt is written all over his face. Even a Neanderthal like Beppe Lopato can see it.

“I hope the other guy looks worse.”

The swelling has subsided and the bruises are beginning to fade from purple and green to yellow. The cut on Frankie’s lip hasn’t completely healed. He’d considered covering the damage with makeup, a little foundation, something subtle, of course. But in the end he decided to show himself to the world and resort to the tale of an errant taxi running a red light if anyone asks.

“It’s very butch. I like it!”

Frankie doubts his sincerity. Beppe, one of those unfortunate Sicilians who resemble the missing link in a Time-Life series on the history of man, has always been envious of Frankie’s blue eyes and fine features. He’d mocked Frankie in beauty school, calling him Fabian, after the baby-faced erstwhile teen idol from South Philadelphia.

“Are you doing Paul Mitchell? I’m headed over to the booth. Walk with me, Frankie, and let’s catch up,” he says, obviously curious about who’s been using Frankie as a punching bag.

An internationally renowned expert on color application is lecturing in ten minutes and Beppe wants to get a good seat. Frankie begs off, saying he’s signed up for the extensions demonstration at the Matrix exhibit. They part ways, air-kissing, swearing to have lunch or cocktails soon, a promise made and broken every year. Frankie wanders the two acres of concrete floor, from Healing HairCare to Naturceuticals to Satin Smooth Full Body Waxing. His mind is distracted. Nothing registers. He needs to sit for a few minutes, and the “Be a Color Artist, Not a Color Chartist” presentation is as good a place as any.

It’s still 1983 here at the Valley Forge Convention Center Hair Expo and Trade Show and Michael Jackson has never gone out of fashion. Over the years, Frankie’s seen thousands of stylists choreograph their presentations to “Beat It” and “Rock with You.” The kid onstage is shimmying and shaking to “Wanna Be Startin’ Something,” brandishing a pair of shears and a can of hair spray like he’s headed for a high noon showdown. The boy wasn’t even born when Thriller topped the charts and wouldn’t recognize the King of Pop in a picture taken when he still had his own nose. It’s exhausting watching him multitask up there, demonstrating a revolutionary new color system while auditioning for Dancing with the Stars. Frankie’s seen enough and trudges back onto the exhibit floor.

He’s restless, living on caffeine. He’s barely slept since he flushed the Ambien down the toilet, a terrible mistake. Those pills were his opportunity to take the easy way out. It was a rash decision he deeply regrets, forcing him to choose one of the more grisly, and likely more painful, alternatives, any of which is still less terrifying than the possibility of being confined behind bars for the rest of his life, spending the next two or three decades as a caged animal.

An army of bitter and burnt-out old stylists flocks to him, sensing fresh prey. They harangue him with brochures and order forms and discount coupons for the products they’re hawking. He’d had the good sense to hide the color-coded ID badge identifying him as a PROPRIETOR in his pocket, but they’re still circling him like vultures descending on fresh carrion, their instincts sensing he’s a salon owner with a shop to stock and inventory to replenish.

“Francis Rocco Gagliano. You get more gorgeous every year. And that black eye is sooo sexy!”

He’s staring into a blank slate of chemically induced preternatural youthfulness. He loves her cut, though, a no-nonsense Klute-era Jane Fonda shag that looks shockingly hip and contemporary.

“It’s me, Estelle Prince!”

“Oh my God. What’s the matter with me?” he apologizes, though she’s been remodeled beyond recognition. “You look incredible.”

She assumes he means it as a compliment. Parts of her face, the moving ones, seem to be made of putty. She seems perpetually startled, a talking wax doll who’s been zapped by a stun gun. She babbles on, much ado about nothing, and he shakes his head in agreement though his mind is elsewhere and he doesn’t hear a word she says. He knows now it was a mistake coming here. They’ll all agree in hindsight he was acting strange at the Hair Show. Most people will say they didn’t know he had it in him. A few will claim the news came as no surprise. He wouldn’t look me in the eye, now that I think about it. It’s a damn shame, but what can you expect if you get mixed up with those kind of people? But he foolishly agrees to join Estelle for a glass of wine after the “Beyond Basic Foiling” presentation. They embrace, promising to meet in forty-five minutes. He waits until she disappears into the crowd and turns toward the exit, attempting a quick getaway, and nearly collides with the young woman who steps in front of him, blocking his way.

“You cannot say no. I’m going to make you an offer you can’t refuse.”

She’s the very model of scientific efficiency, dressed in a crisp white lab coat, cradling a clipboard in the crook of her elbow. She’s wearing I-mean-business eyeglasses, the tortoise frames suggesting the serious dignity of a wise owl; her hair is pulled back in a ponytail with a few tendrils liberated to flatter the strong cheekbones of her lovely face.

“You get a fifty-dollar honorarium and a sample selection of our top-of-the-line hair product. And you’ll leave the show today a new man with a brand-new look. Satisfaction guaranteed.”

He’s about to politely decline her generous offer when she introduces him to the stylist, licensed as both a barber and a cosmetologist, an expert, she assures him, in both professions. Vince is his name, and his Clubman Classic aftershave, crisp, antiseptic, is vintage 1967, the year Frankie’s papa put his seven-year-old son to work sweeping clippings from the barbershop floor and emptying ashtrays heaped with smoldering cigarette butts. His younger brother, Michael, had resented being conscripted into Papa’s labor force as soon as he was tall enough to push a broom, but Frankie never minded. He would linger in the shop after his chores were done, too young yet to understand why he was drawn to the longshoremen and refinery workers who sat flipping through ancient issues of Sports Illustrated and Car and Driver, crossing and uncrossing their legs with casual grace as they waited their turn in the barber chair. Their loud, deep voices rumbled as they argued about sports and politics. They called him Little Pitcher, a reminder that certain language wasn’t meant to be overheard by Big Ears, and teased him about his long eyelashes and wavy hair, saying it was a shame Frankie hadn’t been born a girl, all those good looks going to waste on a boy. Forty years later, he’s still aroused by the memory of their unfiltered Pall Malls, the Chock Full o’Nuts on their breath, and the Brylcreem they used to landscape their hair.

“You game, my friend?” Vince asks. “Feeling brave today?”

He’s neither short nor tall; broad through the shoulders and barrel-chested. He’s thick around the waist, not quite potbellied, certainly not sloppy but carrying a few extra pounds; his loose Hawaiian shirt, a relatively sedate design of bright green palm leaves on a navy background, is a generous fit. His forearms are sturdy, built for heavier labor than barbering, and dusted with a fine spray of sun-bleached hair. The visible tattoos are Navy port-of-call vintage, clearly not the handiwork of a punk-rock skin-art boutique. He’s wearing Levi’s 505s, full cut, and Sketchers, probably with inserts for extra support. He’s a man who’s clearly comfortable in his own skin. His blunt, still-handsome face is branded with a raised, flaming-red scar from his right earlobe to the corner of his mouth, a warning he’s a man with a past: mysterious, dark, dangerous, the survivor of a bar fight or a prison term in the Big House or a tour of duty in the first Gulf War.

For all his foreboding appearance, Vince is a friendly enough guy, approachable. He tells Frankie he has fifteen years experience cutting hair and owns a small shop in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, where he makes a good living doing volume in ten-dollar haircuts. He recently moved in with a “special lady” he met in his motorcycle club and he’s paying to put her through beauty school. He suggests a much shorter cut for Frankie, to give him a more masculine look. He’ll try a fade on his neck and up the sides, something that won’t need any upkeep or grooming. He’d like to bring a little color back, nothing terribly dramatic. He suggests they try a Number Two solution for a natural-looking blend.

“Get ready to rock and roll!” Vince says as he leads Frankie to the chair.

His gruff but soothing voice preaches the gospel of men’s styling as a life raft in tough economic times to a rapt audience gathered for the demonstration on his willing guinea pig. Do the math: more potential bookings per week, none longer than twenty minutes and most of them in and out in ten, more visits per year, every two weeks for most men, none less frequent than monthly. Pay close attention now, he cautions, demonstrating the most effective way to use a number one guard on his clippers while eulogizing the dying art of scissors-over-comb. He promises his skeptical audience the product he’s about to demonstrate will break the final barrier of a guy’s reluctance to color his hair. It’s a simple shampoo, leave it in five minutes, a quick wash, and they’re out the door. The construction workers and long-distance haulers who come into my shop wouldn’t be caught dead under the dryer.

Frankie surrenders to the strong hands massaging his scalp. Vince lowers the chair to rinse his hair with warm water and briskly dries it with a barber towel.

“So there you have it. A fresh new look in nineteen minutes.”

The audience approves of the results, nodding and throwing a thumbs-up.

“So, whaddya think?” Vince asks, spinning the styling chair so Frankie can face himself in the mirror.

He’s showing more skin than he expected, especially in the close-cropped area above his ears. He likes the cut; it’s a clean look, almost military. And the color is soft and natural, even to his critical professional eye.

“Thank you, brother. Don’t forget to pick up your free sample bag,” Vince says as he shakes Frankie’s hand and quickly dismisses him, turning to introduce himself to his next challenge, a faux-skateboarder/bike messenger with spiky extensions who’s about to be transformed into G.I. Joe. Frankie tosses the bag into the nearest trash can as he walks to the exit. He won’t be needing conditioners or gels to maintain his “brand-new look.” He hadn’t bothered to collect his fifty-dollar honorarium. There’s nothing to buy and no use for money where he’s going.

An overdose would have been calm and peaceful, but his internist won’t refill the Ambien and the Ativan. She suspects he’s abusing since she called in a month’s worth just last week. Swallowing a bottle of an over-the-counter drug wouldn’t be lethal and he would end up in the ER, having his stomach pumped. He doesn’t own a gun and his hands would shake too badly to attempt slitting his wrists. Drowning would be painless, but those few moments before he loses consciousness would feel like an eternity, enough time to regret what he’s powerless to reverse as his lungs fill with water. Same problem with jumping off a building. He doesn’t want his life passing before his eyes as he falls twenty stories. Hanging is too risky. If his neck doesn’t snap, he’ll strangle to death, clutching at the rope and gasping for breath.

He’s considered all the alternatives and the swiftest, most efficient way to do this is to step into the path of an approaching train. He’ll leave the car in the wasteland of cargo terminals and storage units surrounding the airport and walk to the railroad tracks with his iPod set at maximum volume, Stevie’s magical voice singing “Rhiannon” and “Gold Dust Woman,” the last sounds he wants to hear as he leaves this earth. In a few hours he’ll know whether there’s a heaven waiting to welcome him or a hell to which he’ll be condemned for taking his own life or if it’s all just a black nothing. He’s collected all of the official documents Michael will need to put his affairs in order—his will, the deed to the building, the insurance policies, the numbers of his various bank accounts. They’ll find his wallet with all his ID on the driver’s seat of the abandoned car. This morning he locked the doors of the home he’s lived in his entire life for the very last time. He didn’t leave a note. His reason will be obvious. Not immediately, but soon enough.

“Frankie! Frankie! Did you forget our date?”

Estelle Prince, laden with shopping bags full of brochures and samples, is chasing him, teetering on her skyscraper stiletto heels.

“Should we take one car or two?” she wheezes.

It’s likely the most exercise she’s had in years and left her short of breath. Thankfully, she doesn’t object when he suggests they drive separately. He considers losing her in traffic, but fortifying his resolve with a liberal dosage of alcohol isn’t a bad idea. Estelle insists the local outpost of a national chain of “authentic Italian bistros” has a decent wine list. A lone salesman is nursing a bottle of beer at the bar and two well-heeled blue-haired old ladies are lingering in a booth. The hostess seats the latest arrivals, offering menus, which Estelle refuses, saying they’re just having a drink.

“We have a nice selection of wines by the glass,” the young lady offers.

“We need more than a glass. You don’t have anywhere you have to be, do you, Frankie? Let’s share a bottle. Red or white?”

Frankie shrugs and says he’ll be happy with whatever Estelle chooses.

“Chardonnay,” she predictably instructs the server. “The one from the Central Coast. Not one of those ridiculously expensive bottles from Sonoma.”

“Bring us the Cakebread Cellars. My treat, Estelle.”

His last glass of wine should be a good one.

Estelle’s not about to argue with his generosity. Frankie waves away the cork and tells the server to pour. He’s sure it’s fine.

“What are we celebrating?” Estelle asks, proposing a toast.

“Nothing. Nothing at all.”

“We have to celebrate something! Let’s toast your new look then. Oh, sweetie, the color takes ten years off your age. I hope you’re ready for all the young men who are going to be running after you!”

She’s far too self-absorbed to question Frankie’s insistence on quickly changing the topic to her favorite subject—herself. All he’s called upon to do is occasionally nod his head in agreement to encourage her to keep the one-sided conversation going. He settles back and lets his mind wander, allowing her to vent about her philandering soon-to-be-ex-husband and the crushing legal fees she’s paying her attorneys to punish him in the divorce settlement.

“We’ll have another bottle,” he tells the server as she approaches the table.

“Are you planning to get me drunk so you can take advantage of me?” Estelle teases.

He laughs mirthlessly and swallows a mouthful of wine. When the time comes to settle the bill, he’ll be as ready as he’ll ever be. He remembers a line in a song about finding courage in the bottle, but doesn’t recall who sang it. Estelle says she’s getting light-headed and places her hand over her glass when he offers a refill. More for me, he thinks. The alcohol doesn’t exactly transform fear into courage like the song promised, but it’s loosening his grip on any remaining doubts about stepping on to the railroad tracks. He needs to finish the job before the effects of the wine wear off and cowardice and misgivings weaken his resolve.

“Are you sure you’re okay to drive?” Estelle asks as they walk to their cars.

He brushes off her concerns. He’s not stumbling or slurring his words, but he’s clearly under the influence, which, of course, is exactly where he needs to be.

“Don’t worry. I’ll stop for a coffee at the Wawa before I get on the expressway. I promise.”

It’s a few minutes past five, according to the digital clock on his dashboard. The evening rush hour is building to full force and traffic is at a near standstill. At least he doesn’t have to worry about drifting between lanes at sixty-five miles an hour. He squints and peers over the steering wheel, not trusting his ability to accurately gauge the distance between his front bumper and the brake lights of the car ahead. He’s confused by the jumble of directional signs overhead. South to West Chester. The Pennsylvania Turnpike to Harrisburg and points west. East to Center City Philadelphia and the Philadelphia International Airport. That’s the direction he needs to travel. Distracted and anxious, he nearly misses the access road to the interstate and makes a sharp right. In his confusion, he’s misread the road signs and doesn’t realize he’s trying to enter the expressway on the one-way exit ramp until he hears the siren and sees the flashing blue dome light in his rearview mirror.

MICHAEL (EVENING AND INTO THE NIGHT)

“You know, I could just put you out in Norristown and let them press charges, if that’s what you want.”

News travels fast and bad news flies at the speed of sound. The Upper Merion Township police had contacted the young on-call prosecutor of the Office of the District Attorney for Montgomery County, who then called her supervisor for guidance after Frankie had disclosed his brother, Michael, was Chief Deputy District Attorney in the neighboring county. After a brief phone conversation between Michael and his peer, the officer in charge told his partner to tear up the report he’d begun to write and released Frankie from custody. Michael made arrangements to pick up Frankie’s car in the morning. He’d assumed Frankie was too embarrassed to face Michael’s wife and son (a nine-year-old asks a lot of questions) when he’d refused the offer to spend the night in their guest room in Wayne. He’d pleaded to be dropped at the nearest station so he could take a train back to the city. He’d only agreed under protest to allow Michael to drive him home and has been sullen and hostile the entire ride.

“So I take it you’re not talking to me. Fine. I won’t ask again what happened to your face. Last month you tripped. Now you tell me your taxi ran a red light. If you ask me, I’d say someone’s put the maliocch’ on you.”

Michael’s sarcasm fails to get a rise out of his brother.

“Jesus, how long have we been sitting here? At this rate I won’t get home until midnight.”

He’s staring at a seemingly endless ribbon of red taillights on the road ahead, waiting for the traffic update on news radio. The headlines of the day are the same as yesterday’s and the day before that. Natural disasters. Military skirmishes in distant lands with unpronounceable names. Domestic tragedies. Children killed in crossfire between street gangs. Hillary. Obama. The Dow Jones. The five-day weather forecast for the Delaware Valley.

Somewhere in that mash-up between the important and the inconsequential, all stories read in a comforting monotone, he’s startled to hear a sound bite of his own voice. Was it only this morning he’d spoken to the press on behalf of the District Attorney, announcing the decision “… to not seek a retrial of the first-degree murder charge of Tommy Corcoran, whose capital conviction on that count was recently overturned by a federal court. Corcoran continues to serve a life sentence without parole on the remaining charges. Now on to traffic and transit. Eastbound traffic is experiencing forty- to fifty-minute delays from 202 to the Vine Street underpass due to an overturned tractor trailer.”

What began as a trying day is ending on a bad note. Michael’s unhappy about being forced to suffer this endurance test on the expressway. It would have been perfectly reasonable, not to mention convenient, for Frankie to stay the night in Wayne. There’s only one explanation for Frankie’s anxiety about rushing back to the city. He’s worried that goddamn little Mexican illegal is pouting in front of the television, feeling neglected and abandoned. It astounds Michael that his brother trusts the kid with the key to his house and thinks nothing about leaving him there alone.

“We could sit here for hours,” Michael grumbles. “Call him and tell him you’ll be back as soon as you can.”

“He isn’t there.”

“Where is he?”

“He’s gone.”

“I hope you told him not to come back. That little shit. I knew this was going to happen. How long did he smack you around before you gave him what he wanted? How much money did he squeeze out of you before saying adiós?”

He immediately regrets his angry, aggressive tone. He’d intended to give Frankie time to recover from the shock of being arrested before resuming the interrogation about this fresh set of bruises and split lip. He feels as if he’s kicking a wounded puppy.

“It doesn’t matter. He’s gone. He’s gone and he won’t be coming back,” Frankie says wearily.

“He’ll be back when he needs a quick cash infusion or a roof over his head. And when he shows up again, I’ll call the authorities myself. I mean it, Frankie,” Michael swears as traffic begins to move, a crawl to be sure for the next mile or two, then slowly gathering steam as they pass the accident site.

Michael and his wife need to start throwing age-appropriate gentlemen with steady incomes at Frankie until one finally sticks. Looking back, he should have appreciated the fifteen years of relative peace and quiet when Frankie was involved with that pompous alcoholic high school teacher. He should have been less critical, more welcoming, of the harmless old fool. Sometimes he thinks Frankie believes he’s never really accepted his lifestyle. But Michael stopped resenting his brother’s sexuality years ago, though he still isn’t going to be marching in any parades to celebrate it. It’s Frankie’s poor choices and naïveté that make Michael uncomfortable. He wouldn’t take the odds against Frankie running into his own Tommy Corcoran someday and ending up like the ill-fated Carmine Torino. His worst fear is that this Mariano is just a test drive for a more lethal liaison yet to come.

“I don’t know how you do this every day,” he complains, grow- ing more frustrated by the minute.

He’s circling the block where he and Frankie grew up, searching for that elusive place to park within walking distance of Eighth and Carpenter and the house where they lived as boys. Years of suburban living have dulled his parallel-parking skills, but he manages to squeeze the car into a tight space, much to the horn-blaring frustration of the driver trying to pass him on the narrow street. He hasn’t eaten yet, having gotten the call from his colleague in the Montgomery County office before dinner, and insists they stop for a slice. Standing at the register, his stomach rumbles and he orders an entire pie, large, half sausage, for him, half mushroom, for his brother.

“What are you doing?” Frankie frets as the girl at the cash register counts out Michael’s change.

“I thought we’d go back to the house and share it. Do you have any cold beer? I’d settle for a Bud Light. For me. You’ve had enough booze for one day.”

“You don’t need to come back with me. I just want to go to bed,” Frankie insists. “It’s been a terrible day and I want it to be over.”

He seems a bit too despondent to Michael for the circumstances. He’s assured Frankie no DUI charges will be filed. No report will be made. The arrest never happened. There won’t be any points on his license or need to attend a mandatory alcohol counseling class. No one will ever mention it again. He wonders if Frankie’s on some medication that’s causing him to act strange. He realizes he has to piss too badly to wait until they’re back at his brother’s house.

Frankie’s gone when he emerges from the men’s room. Something feels out of kilter, ominous even, and he wonders if it’s safe for Frankie to be alone. He grows antsy during the interminable wait before the counter girl announces his order is ready. He opens the box and practically swallows two slices whole as he walks back to the house. He tries slipping his house key into the locked door of the private entrance in the alley on Carpenter Street, but the blade resists sliding into the keyhole. The shop key doesn’t open the Eighth Street entrance, Frankie must have changed the locks after the kid took off and forgotten he hasn’t given Michael the new keys. He sets the pizza box on the sidewalk and dials his brother’s number on his cell, but Frankie doesn’t answer. So he stands in the middle of Eighth Street and shouts his name. The lights are burning on the upper floors so he knows Frankie’s in there.

He’s surprised some neighbor trying to sleep isn’t shouting profanities through a bedroom window. A strange, cold fist grips his heart. He tries calling Frankie’s cell one last time, then calmly, purposefully, walks around the side of the building and kicks in the back door. He runs up the stairs, taking two and three steps at time, until he reaches the bathroom off the master bedroom on the highest floor, where he finds his brother slumped on the commode, cradling his head in his hands. The ceramic lid of the toilet tank is lying on the floor, near the tub. Frankie looks so pitiful and helpless sitting there, needing comfort and reassurance, and all Michael has offered is an unpleasant harangue and criticism.

Frankie barely resists as Michael walks him to his bed. He doesn’t protest when his younger brother unbuttons his shirt, unzips his pants, and takes off his shoes. He’s lying in bed, his eyes wide-open, when Michael turns off the light and urges him to try to sleep. He calls his wife with the good news that the parasite is gone. The bad news, though, is Frankie’s acting odd and Michael doesn’t want to leave him alone overnight. Something doesn’t feel right. I think he colored his hair. No, I didn’t ask him about it. He cut it too. It’s shorter than he usually wears it. He doesn’t look like himself and he sure as hell isn’t acting like himself. He asks if his son is disappointed. Michael had promised him a trip to the mall after dinner to buy a new pair of sneakers. The Nikes Danny’s been wearing have fallen out of style. Tell him we’ll go tomorrow night. I love you, too. Talk to you in the morning. He hopes there’s beer in the fridge and he’ll finish off that pizza if some street dog hasn’t run off with it. But first he needs to secure the back door. The tools and nails are in the basement, likely untouched since the last time he did a minor repair.

Everything down here is just as he remembers. The damp moisture of the earthen floor. The metal storage shelves, odd pieces of furniture and broken lamps, the wide, deep freezer chest, an ancient Frigidaire model, antediluvian, but still serviceable. His eyes are slow to adjust to the harsh light of the bare ceiling bulb and he slips in a puddle underfoot, noticing an odd smell, fetid but not overpowering, the distinct scent of meat beginning to rot. There are two trash bags on the floor, not full but securely tied. He opens one and finds chicken breasts and cuts of beef soaking in water and blood. The freezer must be broken, despite its gently purring motor.

“What the fuck are you doing down there, Mikey?” Frankie shouts from the top of the stairs, his voice shrill and twisted in his throat as he races down the steps, sweating and gasping for breath.

“You need to replace this goddamn freezer.”

“There’s nothing wrong with the freezer,” Frankie insists, grabbing the trash bag from his brother’s hand. “Go upstairs and I’ll clean up this mess.”

“Let’s put this shit back before it stinks up the entire fucking house,” Michael says, opening the lid before Frankie can stop him. A blast of arctic air slaps his face and he blinks and jumps back, confused, staring at Frankie in disbelief, not trusting his eyes, needing a moment to gather his wits before confirming that, yes, Frankie’s little Mexican is lying in the freezer, shrouded in frost, his twisted and contorted remains a snug and cozy fit.

The Boys from Eighth and Carpenter reprinted here by permission of Kensington.