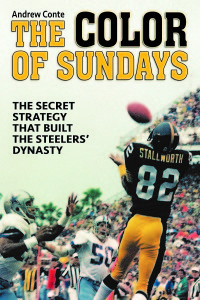

Littsburgh is thrilled to be able to share with you an excerpt from The Color of Sundays: The Secret Strategy That Built The Steelers’ Dynasty by Andrew Conte!

The official launch party for The Color of Sundays will on October 6th at Clark Bar & Grill, and the author will be doing promotional events through November. For more information and updates on where you can get your books signed, check out Andrew Conte’s blog…

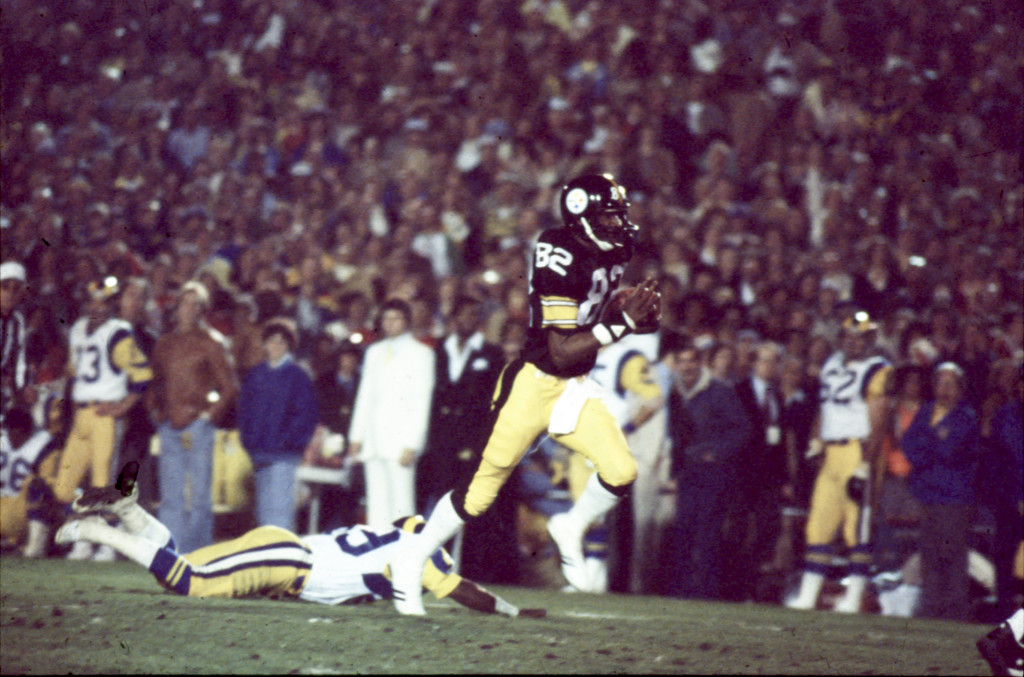

Walking across the football field at Alabama Agricultural & Mechanical University, John Stallworth felt droplets of water from the grass seeping into his cleats, and he shivered at the late-fall chill in the air. One of his football coaches stood with a couple of other players already warming up, but Stallworth hardly noticed them. He knew that the National Football League scouts waiting on the cinder track surrounding the field had come mainly to see him. This would be his only gauge for measuring himself: Run fast enough – covering 40 yards in 4.6 seconds or less – and he might have a chance to play as a professional; run even a tenth of a second slower, and he might not.

Walking across the football field at Alabama Agricultural & Mechanical University, John Stallworth felt droplets of water from the grass seeping into his cleats, and he shivered at the late-fall chill in the air. One of his football coaches stood with a couple of other players already warming up, but Stallworth hardly noticed them. He knew that the National Football League scouts waiting on the cinder track surrounding the field had come mainly to see him. This would be his only gauge for measuring himself: Run fast enough – covering 40 yards in 4.6 seconds or less – and he might have a chance to play as a professional; run even a tenth of a second slower, and he might not.

The scouts represented professional teams such as the Chicago Bears, Detroit Lions, Pittsburgh Steelers and others. They were among the only white men on the campus of the small black college in Normal, Alabama. By late 1973, the nation’s historically black schools no longer remained a secret: NFL insiders knew at least a few of the athletes could play at the next level, as professionals. The challenge was finding the right ones. Stallworth glanced over at the men long enough to see only one black scout, tall and lean with his hair in a thick afro. Stallworth didn’t know the man but guessed he must be Bill Nunn Jr.

Alabama A&M’s coaches seemed to know Nunn well. He had been coming to the campus for years. Recently, he had been scouting for the Steelers, but before that he had worked as a sports writer at the Pittsburgh Courier, a black weekly newspaper with more than a dozen editions across the country – in Seattle and Los Angeles, Miami and New York. Even then, after joining the Steelers, Nunn still picked the nation’s 22 best black college football players for the newspaper’s All-America team. When the NFL purged all of its black players in the 1930s, young men at black schools still could dream of having their name appear in the Courier. Then after the war, even after teams added blacks back to their rosters, one and two at a time, the Courier’s All-America team offered the best chance to be noticed. At small schools like Alabama A&M – not known for producing NFL players – Nunn represented a lifeline.

Stretching out his legs in the end zone, Stallworth felt goose bumps break out across his skin as he took off his sweatshirt. The air felt cold for the South, in the upper 40s. He thought about everything that had led to this moment. Growing up two hours away in the former state capital of Tuscaloosa, Stallworth had imagined playing football at the highest levels. He spent Saturday afternoons watching the hometown team at the University of Alabama, dreaming of catching perfect spirals from Crimson Tide quarterbacks Joe Namath and Kenny Stabler.

In reality, Stallworth knew it could not happen. The United State Supreme Court had ruled against segregation when he was a child, and Congress outlawed discrimination based on skin color just days before his 12th birthday. But Alabama football remained all-white throughout his high school days.

Stallworth first attended all-black Druid High School, but the football coach said he was too skinny to play. So when a court order freed up students to choose where they attended, Stallworth transferred across town to the mostly white Tuscaloosa High School as a sophomore. The seniors that year included the school’s first black graduates. On Friday nights, Stallworth looked into the stands to see fans waving Confederate flags and he listened to the marching band playing “Dixie.” Stallworth had some close friends among the white students, so he figured people waved the rebel flag because they always had, and not because they really wanted the South to rise up and reclaim slavery.

Even if the University of Alabama had been fully integrated, Stallworth would have had a hard time making the team. Tuscaloosa High School won just one game in each of his final two seasons. Stallworth saw himself as a wide receiver, but Tuscaloosa did not have a strong quarterback. The coach convinced him that it made no sense to try catching balls if no one could throw them. Instead, Stallworth played as a tall, lanky running back. It was not a good fit and he had been lucky to find a college looking his way at all. The father of a teammate had attended Alabama A&M, and Stallworth used the connection to introduce himself to the football coaches and ultimately to win an athletic scholarship. Alabama A&M’s coaches said they had expected other schools to recruit Stallworth, but he knew he had been lucky to end up in Normal. Like many other athletes, he had little other chance of attending college.

Standing on the field at Alabama A&M’s stadium with the scouts watching, Stallworth wondered whether he would have an opportunity to move up in the sport again. Everything hinged on that one-tenth of a second, the difference between winning the scouts’ attention or not.

At the goal line, Stallworth crouched into a sprinter’s start and looked down the field where the scouts stood waiting with notebooks and stopwatches in hand. Running on the damp turf would not be ideal for a fast time, but going on the cinder track would have been worse. At the signal to start, Stallworth broke out of his stance and covered the grass as quickly as he could, his entire future hanging in the balance of those 40 yards.

As he crossed the finish, Stallworth didn’t even look up. He could tell from the men’s reactions – their disappointed sighs – that he hadn’t been fast enough. He could feel it. Bent over and still breathing hard, the college senior lacked the confidence even to walk over to the men to ask them about his time, to talk about his chances of being drafted or to ask for a second chance. He stood up, grabbed his sweatshirt and pants from the sideline and quietly started walking back to the dormitory. His moment had ended almost as soon as it had started.

At the other end of the field, the scouts felt the window closing too. They stayed around to see the few other athletes run the 40 yards, but without enthusiasm. The man they had come to see had been a step too slow, barely worth the trip to Normal. Certainly a few black college athletes could play in the NFL, but they had to be better. Stallworth had shown average speed and little charm.

The men folded up their notebooks and put away their stopwatches. Moving as a group, they turned away from the field and walked back toward the parking lot with the cinders of the running track crunching beneath their dress shoes. Nunn, the newspaper man and Steelers scout, walked with them. Life on the road could be exhausting, traveling across the country, stopping at several college campuses a day. The men around him knew it didn’t take much to feel sick, especially in this cool, damp weather.

Nunn started coughing. He wasn’t feeling well, he told the men. He must be coming down with something. It would be his loss, but he would have to stay behind in Normal. He would have to catch up with the other scouts down the road.

Nunn stood alone, coughing in the parking lot, until the last car pulled away. He watched the men pulling out of Normal, and then turned. Without waiting any longer, he started sprinting – back across the cinder track, in the direction of Alabama A&M’s dormitory buildings.

Excerpt and photos reprinted here courtesy of the author. Click here for more information on The Color of Sundays.