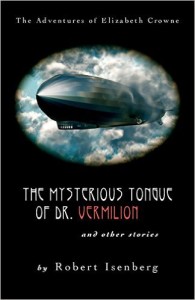

Littsburgh is thrilled to be able to share with you this excerpt from The Mysterious Tongue of Dr. Vermilion by Robert Isenberg, a collection of five connected short stories starring Elizabeth Crowne, a paranormal investigator living in Pittsburgh in 1921 (“It’s like Dorothy Parker meets The X-Files”).

For fourteen years, Robert Isenberg was one of the busiest freelance writers in Pittsburgh. He is author of The Green Season (The Tico Times Publications Group), The Archipelago: A Balkan Passage (Autumn House Press), and Wander, a poetry collection (Six Gallery Press). An award-winning writer, filmmaker, and stage actor, Isenberg has contributed to such diverse publications as Lonely Planet, McSweeney’s, The Tico Times, The Phoenix New Times, and Pittsburgh Magazine.

March, 1921

Maude tiptoed into the kitchen, then stood by the door with her hands folded over her apron. She tried to make herself smaller, to disappear into the yellowed plaster walls.

Maude tiptoed into the kitchen, then stood by the door with her hands folded over her apron. She tried to make herself smaller, to disappear into the yellowed plaster walls.

Flora looked up from her stewpot and scowled. Her oblong face was blemished with rosacea, and her bushy eyebrows narrowed nastily.

“Maude!” she cried. “What are you standing there for? We’ve got work to do!”

“Y-y-y-y-yes,” Maude stuttered, aiming her gaze at the tile floor. “W-w-w-what can I do?”

Flora leaned back, one arm akimbo, the other absently stirring the pot with a wooden spoon.

“You can grab the slop bucket over there,” said Flora, “and take it to Ward Seven.”

Maude trembled. “But it’s… it’s…”

“It’s what?” Flora spat. “Speak up!”

“It’s Thursday, ma’am. Isn’t it Helen’s turn?”

“Helen didn’t start her shift today,” grumbled Flora. “She’ll be lucky if she’s ever let back in. Lazy good-for-nothing. So it’s your turn, unless you want to try the breadlines, too.”

Maude shook her head vigorously, and her dark hair wobbled beneath a tightly tied headscarf.

“Good then! Now go.”

As Maude approached the so-called slop bucket, she drew a second kerchief from her apron pocket and wrapped it around her face. Even from a few paces away, the rancid smell was overpowering. She had taken care to soak the fabric in water and baking soda before leaving her dormitory, but the stench still seeped through. The “bucket” was really a metal basin, long and wide enough to bathe a toddler. Maude was instructed not to remove the cloth towel that covered it, but whatever the basin contained had stained the towel a sickly maroon.

Maude was a gangly 25-year-old, barely strong enough to open the sanitarium’s heavy doors, so when she grabbed the basin’s handle, she struggled to drag it across the floor. She moved in fits and starts, trying to avoid eye contact with Flora, who glared at her menacingly from behind her pots and pans. The room felt more like a dungeon than a kitchen, and the air was thick with steam and the aromas of boiling food. But Maude hated to leave that room, for the corridor beyond bore so much worse.

Inch by inch, Maude pulled her ghastly cargo down the endless hallway, whose brick walls looked like melting wax in the glum electric light. Behind each iron door, Maude heard the moans and shuffling of invisible bodies, the cackles of madmen mixing with the liquidy coughs of tuberculosis. She struggled to ignore the things she heard; the disparate human noises harmonized into an awful din, which echoed in the empty tunnel and followed Maude all the way to the final gate.

She fumbled with the skeleton key, then finally slipped its jagged head into the lock. She opened the door and yanked the slop bucket into Ward Seven.

The chamber was as big as a train station, with high vaulted ceilings and a cul-de-sac of caged openings. Only the common space was lit; each recess was saturated in darkness, invisible beyond their steel bars. But Maude could hear the rustling in the shadows, human clamor that grew exponentially louder, accompanied by a gathering cacophony of grunts and growls.

Maude trembled so severely that she could barely force herself forward, and her bent body was so exhausted from its effort that she wanted only to stop. But still she pulled the basin forward, into the middle of the vast chamber, where the concrete floor was marked with a single, painted X. When she finally positioned the basin, she wanted to curl into a ball and shut her eyes, to pretend that this was not her life, but the sounds of smacking lips and clanging bars roused her from fatigue. She started to walk toward the door, then picked up her pace, until her oversized shoes clouted frantically against the floor.

Then she did as instructed: She flung herself into the corridor and pushed the iron door closed. Her tiny lungs heaved for breath, and she slinked to the rusty lever built into the wall. She grabbed the handle, just as she’d been told to do, and pulled it downward.

She heard the grinding noise within the invisible chamber, a dozen gates sliding open at once. The automated machinery groaned and squealed, and when the doors had synchronously opened, they boomed into place, echoing profoundly. That was the sound to signal Maude’s departure. She should return to the kitchen now, to chop overripe cabbage and carrots. She should spend the rest of the night mixing flour into the tasteless porridge the asylum fed its patients. She shouldn’t so much as turn around. Just go back, Maude, she’d been told. Be a good girl and don’t make a fuss. What happens in Ward Seven is no one’s business but mine.

But she didn’t turn around. She stayed there, seized by curiosity. Maude had always followed orders, had always accommodated the people around her, but tonight she was guided by a unique desire. She inched toward the iron door. She heard the sound of skidding feet and ghastly voices. Maude had seen this door a hundred times before, yet she had never really registered the tiny rectangle in its center. A hatch, only the size of an envelope, which could slide sideways, like a speakeasy grille. She reached out with quivering fingers and grasped the knob on its side. She pulled—but the hatch only jiggled in place. She pulled again, this time with all the force she could muster, and it flew open. Maude was skinny but not tall, and she had to stand on her toes to peer through the rectangular space.

What Maude saw in that moment froze her to the marrow. She could almost feel her thinning blood, the stopping of her hummingbird heart, the contraction of her every organ. Terror stormed through her, and impulsively she groped the knob and yanked, but the hatch didn’t budge. Her eyes filled with stars, and her legs wobbled. She knew that she should faint, but then she heard a tiny voice of reason—Hold on, Maude! She couldn’t faint, or they would see the open hatch, her unconscious body crumpled on the tile, and everyone would know she had broken the rules. She had to fight this sensation. She had to keep herself together.

Maude pulled once more, and the hatch slid reluctantly back into place. The horror vanished from her vision.

Yet the sound persisted: wet, sloppy munching, dozens of maws gnashing all at once, the scrape of rotted teeth, the whine of flesh separating from bone.

Maude backed away, unable to breathe, feeling dizzy and sick, but still she managed to turn round, arms outstretched before her as she sprinted down the corridor, her ears deafened by the wails of madmen in their cells…

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author.