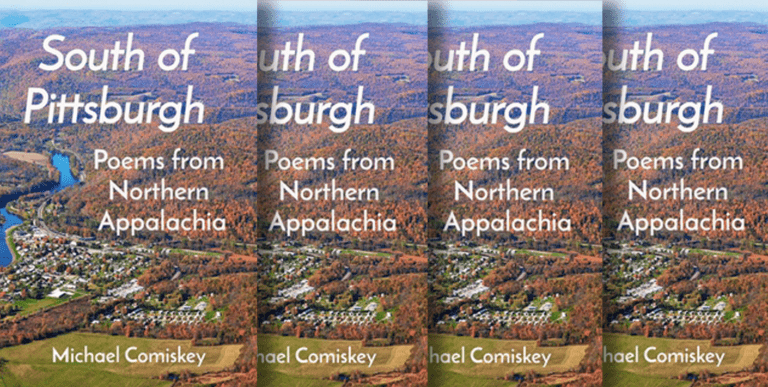

From the Publisher: “This volume of Northern Appalachian poetry employs many traditional and modern poetic forms to survey the human and natural landscapes of that unique and often overlooked region. Featured forms include the sonnet, ballad, haiku, ode, villanelle, elegy, found poem, epigram, narrative poem, and blank and free verse. Topics are as varied as the delicacy of the region’s wildflowers, the devastation wrought by mountaintop removal mining, Northern Appalachian folklore, and the state of the region’s working class…”

More info About the Author: Michael Comiskey is a lifelong southwestern Pennsylvanian and a retired professor of political science and economics. His poems have appeared in The Northern Appalachia Review, The Lyric, Rune, and Prize Poems 2023 (Pennsylvania Poetry Society, Inc.).

Author Site

Those who find the winter chill adverse

might rue that time of year whose essence

is waning warmth and light, and desiccation;

yet even they applaud the transformation

of pervasive green to autumnal fluorescence—

the most scenic senescence in the universe—

and bask in the prospect of settling down

to the prescribed perfection of the year,

when all of nature resolves as it should.

And in that placid atmosphere one could

almost swear that all across the hemisphere

peace and pleasant harmony abound.

Then dying leaves engender a disquieting ferment;

the body craves a dwindling sun

that scantily suffices.

No conjured intellectual devices

thwart apprehension of a year soon done

through ineluctable descent.

All those scarlet leaves turned umber

stir wistful thoughts of days gone by

when all the best tomorrows lay ahead;

and one must ask, as Hamlet: To dread

the deepening chill come nigh,

or concur in wintry slumber?

Clean and Green

With New Technologies

Big Morgan Mountain stood three hundred million years,

and saw a thousand ice sheets come and go.

Its slopes held hardwoods nine flights high.

They stripped the trees first.

Then four hundred foot

of mountaintop

—overburden—

was blown through the air

and dumped in the hollows.

A dragline cut 29 inches of

clean coal

from the carcass.

Now a grey stump

two miles square

greets the eye.

An earth and slate dam,

with its deepening pool

of black, sulfurous

coal-wash water sits

above the valley.

In castrate hollows

seep orange, oozy eddies

of iron pyrite—

fool’s gold.

But who is the fool?

And who has the gold?

Nothing can live

in the alkaline soil.

A Mars lander could come here

and not know the difference,

except for the Astroturf softball fields

shown on TV.

You know the ones—

they’re lighted at night.

Ode to Trout Lilies

“Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow;

they toil not, neither do they spin: And yet I say

unto you, That even Solomon in all his glory

was not arrayed like one of these.”

From the Sermon on the Mount

(Matthew 6:27-28)

King James Version

Consider eastern Erythronium,

known better as the yellow trout lily.

It thrusts up leaf-like cotyledons

in the spring—lancelike, smooth, elliptical—

of purplish puce and waxen green.

Atop the stem the perigoneum

reclines as if asleep, its solitary

flower blooming once in seven seasons.

Bright canary-hued, the tepals—petals—

flair toward earth and flex aloft, their sheen

a beacon in the forest; the pendent

pistil and the purple stamens cling

to slender filaments and seem suspended

in mid-air. Almost incomparably shy,

the precious flower blooms a fortnight

after winter. Utterly dependent

on the pallid sun of early spring,

its transitory tenancy is ended

not by hungry herbivores, but high,

exfoliating oaks that hoard the light.

The lily’s speckled leaves resemble so

a trout that Indians believed it meant

a blooming lily signaled time for us

to fish. One wouldn’t dream that random plants

and animals would closely synchronize,

as few would deem a flower would grow

in such a cold and dim environment.

The lily, though, is myrmecochorous—

its fruit is food for colonies of ants;

thus plant and ant—not fish—do synergize.

As for ants, they have no wish to nurture

lily flowers, nor the flowers to assist

the ants, who take the fragile flower’s fruit

to feed their young in subterranean nests.

But bratty ants won’t eat the seeds therein,

and thus begins a paradigm of Mother Nature’s

celebrated skill at symbiosis:

lily seeds in anty refuse heaps take root.

And thus the dainty lily thrives in forests

cool and dim; it toils not, nor does it spin.

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted without permission.