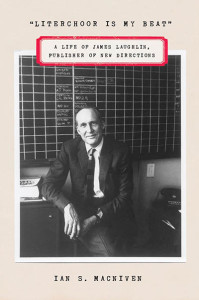

Littsburgh is thrilled to be able to share with you this excerpt from Ian S. MacNiven’s Literchoor Is My Beat, a biography of James Laughlin, founder of the publishing house New Directions, famed publisher of Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tennessee Williams, and many, many more.

Laughlin was born in Pittsburgh — his family owned Jones and Laughlin Steel Company; his childhood home is now a part of Chatham’s campus — and his roots are very much evident in this excerpt, where, upon meeting Gertrude Stein in Paris and learning that the literary life might be harder than he imaged, he muses: “it would be much more sensible… to live in Pittsburgh and work in the steelmill and marry a nice plain girl.”

The following is published here courtesy of the author and Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Part of James Laughlin’s genius, from a very early age, was to meet the people he needed for his intellectual and artistic growth — and to recognize at once their importance to him. At Choate School in Connecticut, young Laughlin read T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Gertrude Stein under the guidance of the poet and translator Dudley Fitts. Except for Eliot, these authors were virtually unread in 1931, but within four years Laughlin would have become a personal friend of all three.

No one meeting Laughlin, six feet six, impossibly handsome, and able to converse in several languages, forgot him. “J,” as he preferred to be known, set sail for France, having committed himself to writing a monograph “explaining” Stein.

– Ian S. MacNiven

Suddenly J’s work on Gertrude Stein took a serendipitous turn. In mid-August J was relaxing beside the Salzburg public Schwimmbad when he noticed a dark-haired sinister-looking man eyeing him.[1. In mid-August as he: JL, address at The Poetry Center, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Feb. 11, 1983, unpublished tape recording, MH.] Deciding that the best defense lay in boldness, J walked over and struck up a conversation. It turned out to be Bernard Faÿ, an eminent French authority on American literature and, coincidentally, Stein’s closest French friend and the translator of The Making of Americans. Faÿ offered to write Stein, then in Bilignin at her rented château ferme, a seventeenth-century fortified farmhouse. Soon J received a “welcome invitation,” open-ended, from the lady herself.[2. “welcome invitation”: JL to MRL and HHL, Aug. 28, 1934, MH.] Faÿ interested J. “A most charming person,” he wrote home, a round little man who deliberately wore ill-fitting and outmoded clothes, Faÿ might well emulate Claudel and become Ambassador to Washington. His manner was a bit fussy, and clearly he manipulated people, playing upon their weaknesses and appetites to advance his own ends. He appeared to be homosexual, so J was careful to cast himself merely as an admiring littérateur.

Suddenly J’s work on Gertrude Stein took a serendipitous turn. In mid-August J was relaxing beside the Salzburg public Schwimmbad when he noticed a dark-haired sinister-looking man eyeing him.[1. In mid-August as he: JL, address at The Poetry Center, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Feb. 11, 1983, unpublished tape recording, MH.] Deciding that the best defense lay in boldness, J walked over and struck up a conversation. It turned out to be Bernard Faÿ, an eminent French authority on American literature and, coincidentally, Stein’s closest French friend and the translator of The Making of Americans. Faÿ offered to write Stein, then in Bilignin at her rented château ferme, a seventeenth-century fortified farmhouse. Soon J received a “welcome invitation,” open-ended, from the lady herself.[2. “welcome invitation”: JL to MRL and HHL, Aug. 28, 1934, MH.] Faÿ interested J. “A most charming person,” he wrote home, a round little man who deliberately wore ill-fitting and outmoded clothes, Faÿ might well emulate Claudel and become Ambassador to Washington. His manner was a bit fussy, and clearly he manipulated people, playing upon their weaknesses and appetites to advance his own ends. He appeared to be homosexual, so J was careful to cast himself merely as an admiring littérateur.

Dallying in Salzburg before going to visit Stein and Toklas, J played upon his seeming-naïve charm, his vocation as poet, his serviceable French and his slight German, his spectacular height and medallion profile, his wavy hair and earnest blue eyes, and was invited everywhere — and all without having to exceed his carefully budgeted allowance. “Suddenly without knowing quite how it happened I found myself transplanted from the poet’s lonely vigil to a tumultuous whirl of high sassiety,” he wrote in an immense letter home.[3. “Suddenly without knowing quite”: JL to MRL and HHL, Aug. 28, 1934, MH.] Everyone he met appeared to have a title or be in some way extraordinary: “one princess (the most stunning looking animal you ever saw with golden hair and eyes like a cat and skin so white you would be sure she were dead. You have seen her picture often in Vogue I imagine…) She has been… very kind to me indeed,” he exclaimed — not very reassuringly — to his parents. He exchanged gossip with Baron and Baroness Engel from Vienna about acquaintances from his days at Le Rosey.[4. J exchanged gossip: JL to MRL?, undated letter fragment, Aug. 1934?, MH.] He saw Harvard lecturer Ted Spencer and his wife Marci, and they spent an evening with Olivia Chambers — “My new passion with the bangs” and an absent husband — and Baron van den Branden, secretary of the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, who argued eloquently with Spencer over Mozart and Beethoven.[5. “My new passion”: JL, diary fragment, Aug. 25, 1934, MH.] “Ted was terribly moved and spoke to me with barriers down, as we came home to the Goldene Rose in the late night munching a hot dog. He said ‘I wish, Jay, that you had somebody in bed with you, either man or woman,’ to which I replied ‘that I had for some time had God in bed with me.’”

In fine spirits J set off for his appointment at Bilignin, driven by Faÿ. The serialization of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas the preceding summer had propelled Stein onto the best-seller lists and the cover of Time magazine. As they approached the château ferme, Stein appeared suddenly in a second-story window, framed by white shutters and a grape vine, her favorite vantage point from which to greet guests. For a few moments she loomed over him: handsome triangular face, profile of a Roman emperor, warm brown hair, brown skirt, blue brocade vest, coral brooch. She set the tone for the visit at once: “You didn’t think I’d ask you here if I didn’t expect you to work,” she stated rhetorically.[6. “You didn’t think . . .”: JL, at The Poetry Center, Feb. 11, 1983.] He discovered that this work was to write press releases for Stein’s coming American tour, to explain in a page of plain language just what she was talking about in each of her six planned lectures. Her drafts were in the form of statements, including “What Is English Literature” — the lady detested question marks — and Stein herself admitted that “they are for a pretty intelligent audience and though they are clear very clear they are not too easy.”[7. “they are for a pretty”: Janet Hobhouse, Everybody Who Was Anybody: A Biography of Gertrude Stein (Doubleday, 1975), p. 155.] J suggested that she might lecture at Choate and persuaded her to prepare a simplified talk for prep school students. The result was “How Writing Is Written.” Each morning when J showed her one of his synopses, Stein would say, “No you haven’t got it do it again.”[8. “No you haven’t got it”: JL, at The Poetry Center, Feb. 11, 1983.] As J painstakingly tried once more to transduce Steinese into standard English, Gertrude would sit with her back to the superb outlook and write with great rapidity in a large notebook. J described it as automatic writing, “Zip, zip, zip.” “That just ain’t art,” he recalled much later.[9. “That just ain’t art”: JL to TM, Nov. 8, 1957, Bellarmine.]

J was not entirely failing in his “work,” as he had at first thought, for some days into his visit he heard Stein announce to Faÿ, “I say, the kid hasn’t done badly.”[10. “I say, the kid hasn’t”: JL to MRL and HHL, Sep. 7, 1934, MH.]

Stein liked to walk in the heat of the day, when most life from oxen to insects had gone silent. She kept up a steady patter, “talking about books that had lived and died as we walked along the hot, green hillside,” calling to the dogs and lecturing J in a “gay contralto” on what made literature last.[11. “talking about books”: JL, Introduction, Gotham Book Mart Catalogue 36 (Robert Alexander Press, 1936), pp. 1-2.] “Can you tell which books of your own time will be read in school by your grandchildren?… When Henry James was writing how many people thought he would come to be considered America’s finest writer?” “Was it,” J ventured, “like so many things, a matter of luck?” Stein gave her wonderful hearty laugh, bounded over a wall after her dogs, and his question went unanswered.

Deliberately, J set out to give his letters to his parents a Steinian plain diction and style:

I like Gertrude very well and she is a great woman but one can never be sure. She knows more about writing and words than anyone else has ever known surely and yet sometimes I think there are things we live which a word cannot tell even when, as in her writing, you give it not its name but the word that makes it be without repeating it. She is very nice to me and very frank… and she has a smile in her eyes that is second only to Whitehead’s. I have learned more about writing in these few days than ever I have known before. Things that I have felt inside me about the writing of poetry and prose and have never been able to express or fully understand, these things she has made clear to me. I have always had a trouble with my writing that was a bother to me but I could not understand what it was though I knew well that it was. She explained it to me at once. When you write, she said, don’t let your hand get ahead of your head. That is what has been troubling me for so long… I will always I know want to use words and not be used by them which is the thing that she does.[12. “I like Gertrude”: JL to MRL and HHL, Sep. 7, 1934, MH.]

The purgatorial part of each day that J spent with Stein came during their afternoon drives. “Miss Stein fills the car quite completely though she is not big, but she is like a rock sitting there quite solidly, and she holds the wheel still after driving for thirty years as though it were something she did not quite trust,” J wrote to his parents.[13. “Miss Stein fills the car”: JL to MRL and HHL, Sep. 7 and 10, 1934, MH.] “She drives very fast and very well and never looks at the road but is never in the wrong place.” Gertrude and Alice would sit in the front seats of Godiva, the Model A Ford, while J and Basket, the show-clipped white poodle, and Pépé, the Mexican mongrel, occupied the backseat. The dogs kept licking J, and if he dared to swat one of them, Toklas would turn around and say, “Jay! Be nice to those dear dogs!” Mainly, J was intent on learning from Stein: “The landscape… is what FOUR SAINTS is about. Miss Stein sat and looked at it for a long time and the things that it always made her think of are the things that you saw in FOUR SAINTS” — J and his mother had seen the Virgil Thomson/Stein opera six months before on Broadway.[14. “The landscape”: JL to MRL and HHL, Sep. 10, 1934, MH.] One dictum of hers he was determined to apply to his own writing: “I have learned that in the end it is not what you are writing about but what is written, that is the words that are written, that matter.”

[bctt tweet=”Two Pittsburgh Natives Meet in France: Gertrude Stein (age 60) and James Laughlin (age 19)”]J felt at once chastened and inspired. “You see all of a sudden it is very wonderful to know that you know a person is a complete person absolutely complete and nothing at all left over or wanting,” J summed up Stein — and then himself. [15. “You see all of a sudden”: JL to MRL and HHL, Sep. 7, 1934, MH.] “You see it is all a wonderful thing and I am glad that it has happened but of course it would because these things happen to me I am that kind of person. I am the kind of person who is not very amusing and not very dull and things happen to him and he tells about them not very well but he tells about them.” He also lowered his own expectations: “It has been very nice to know Miss Stein and also it has its drawbacks. Each time you know a great person you begin to know more and more that you yourself are not a great person and that it would be much more sensible… to live in Pittsburgh and work in the steelmill and marry a nice plain girl… At present I wouldn’t lay much money on my literary success… but really I wouldn’t lay much money against my still trying to write because really there is only one thing that pleases and that is knowing and when you are writing and trying to write you are knowing things.”

Despite her dogmatic pronouncements, J would always speak fondly of Stein, whom he recalled as “certainly — practically — the most charismatic person I’ve ever met.”[16. “certainly — practically — the most”: JL on tape, St. Andrews College, 28 Oct 1975.] Stein told J that the test for good books was that they must make the bell ring.[17. Stein told J that: JL interview by Daniel Bourne and Stephen Cape, Gallery 2:4 (April 1981).] This intuitive, inner bell-note became J’s standard for judgment, rather than a book’s adherence to any particular philosophy, style, mode, or ism. And this simple dictum would go a long way toward explaining the eclecticism of the future New Directions, for J, even with his declared intention of publishing “advance guard” literature, would always at heart be an appreciator, not a critic. Ironically, where Stein’s writing was concerned, there was no such ringing: J would never ask for a new book of hers to publish. Stein’s importance to J lay in her artistic integrity, the purity of her stylistic voice.

J usually trusted his own ear, even as a very young man, but this could get him into trouble. Once Stein discovered him happily immersed in Proust. “Jay, how can you read such stuff?” she demanded angrily. “Don’t you know both Joyce and Proust copied their work from my Making of Americans?”[18. “Jay, how can you read”: JL, at The Poetry Center, Feb. 11, 1983.] And when J tried to discuss the Nazi threat at dinner with Stein, Toklas, and some of their French friends, Baron Robert d’Aiguy told him that he knew nothing about wars, “so please hush until you know what you are talking about.”[19. And when J tried to discuss: Alice B. Toklas, What Is Remembered (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963), p. 139.] To J, Stein said that Hitler was “a very great man.”[20. “a very great man”: JL, at The Poetry Center, Feb. 11, 1983.] From the valley below they could hear the rattle of machine guns: a French Moroccan regiment was training. “This is a bad thing but is it a wonderful thing to hear what the war sounds like and not have to be in it,” J wrote to his parents.[21. “This is a bad thing”: JL to MRL and HHL, Sep. 7, 1934, MH.] Stein seemed unperturbed by the threat of war. After eight days, J was on his way to Paris, where he planned to complete his work for her.

It might seem at this juncture that two mighty champions were contending for J’s allegiance and soul. Stein had become fond of him and saw him as a useful agent in her American campaign. Pound assumed that J was firmly in his camp. J might have been fascinated by Stein as a person, and saw that a monograph on her would be a good leg up to his reputation as a literary man, but he did not waver in his primary commitment to Pound.

[ . . . ]

Although J had not completed the study of Gertrude Stein that he had worked on since 1933, he was still interested in her. He headed a page of his Lausanne notebook “Gertrude tips” and wrote down twelve items, some admonitory, others mnemonic.[22. “Gertrude tips”: JL, Laussane notebook, 24, MH.] J had a title for his intended short book: “Understanding Gertrude Stein.”[23. “Understanding Gertrude”: JL, “Understanding Gertrude Stein,” June 17, 1935, Lausanne notebook, 30, MH.] “I think now that I am writing for friends and not enemies,” he wrote. “America is thorough. For nearly thirty years America thoroughly made fun of Gertrude Stein. And now America is thoroughly enthusiastic about her.” Then J articulated a thought that would become a lifelong adage: “The time-lag is inevitable,” he said, referring to the time it had taken from her earliest publications to her achieving a wide audience. “Contemporary writing, the work that really expresses its time, is seldom accepted by the generation it mirrors.” He hazarded a prediction: “It is reasonable to expect that by 1960 her work will be read in schools.”

When J returned to his cahier, it was to discuss Stein at length. He cited her lecture “What Is English Literature” on the decay of the English language and the need to dominate it in order to renew it, and he drew a parallel with Cocteau, who said that he alone “had the moral right to smoke opium as he alone could dominate it.” The same was true for writers and language. “Have you the ‘right’ to be a writer?” J challenged his readers, adding introspectively, “Have I?”

Part of the problem that J was encountering was that Stein refused to be compressed into manageable form. And she seemed to need context. He announced Understanding Gertrude Stein for publication in the winter of 1936, and he claimed that his book would include “parallel trends in contemporary experimental writing,” with chapters on Joyce, Cummings, surrealism, and “Basic English and the Orthological Institute,” treating also linguistics and semantics.[24. “parallel trends”: JL, Arrow Editions, advertising copy in New Directions in Prose and Poetry, 1936.] Having thus painted himself into several corners, J quit. He would never again attempt a work of literary criticism and analysis on this scale.

Both Miller and Stein held temptation before J. Was he willing to cast himself into the lower depths and then make literature out of it? He was able to answer that at once — he wouldn’t live Miller’s disordered life. Stein’s implied offer was more tempting: use the time that wealth allowed him to read “ALL” literature in English, and finally recreate the language.[25. “ALL” literature in English: JL, Lausanne notebook, 37, MH.] If he could only combine it with publishing and skiing! “No artist needs criticism, he only needs appreciation. If he needs criticism he is no artist,” Stein had written in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, and this J quoted with approval in his Lausanne cahier: it was good advice for a future eclectic publisher as well as for scholar or critic or artist.[26. “No artist needs”: Gertrude Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (Modern Library, 1993), 319.] As for his own art, J stopped mentioning a novel about philistine Pittsburgh.

[ . . . ]

Around this time J wrote to Robert Fitzgerald, future translator of the Odyssey and the Iliad, “Gertrude told me quite candidly the other day for my own good that I was one of those guys who had mistaken sensitiveness for something more and that the sooner I jumped off the poetry boat the better I would later be at making steel.” Then J added, “I guess she is about right.”[27. “Gertrude told me”: JL to Robert Fitzgerald, quoted in Penelope Laurans Fitzgerald, “‘…And in the Bond,’” 155.]

J had doubts about not only his poetry but his fiction and his literary criticism. He had found himself unable to get into his novel or to complete to his satisfaction his monograph on Stein. Under the guise of writing about Stein, he had been probing his own suitability for and commitment to fiction and coming up short.

This excerpt and image published courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Click here for more information on Literchoor Is My Beat.